Web scraping - Part 1

Scraping data has two meanings in journalism. In one sense, it means extracting information from just one source, like a web page or a PDF document. In another sense, it means pulling data from multiple pages, like individual profiles of people. A typical workflow for might be:

- Find a list or a way to guess at a list for all of the pages you might want

- Write a program to “crawl” a website to save those pages.

- Extract the information from each page into a database.

Sometimes, though, it’s not even necessary to go that far.

Looking for data on the web can be as simple as good searching. You might find what Rob Gebeloff calls an “JSON miracle”. Or you might be able to just change a few words in a window to get just what you want.

Understanding requests

When you use the search box WITHIN a website, you are usually searching an internal database that hasn’t been indexed by Google.

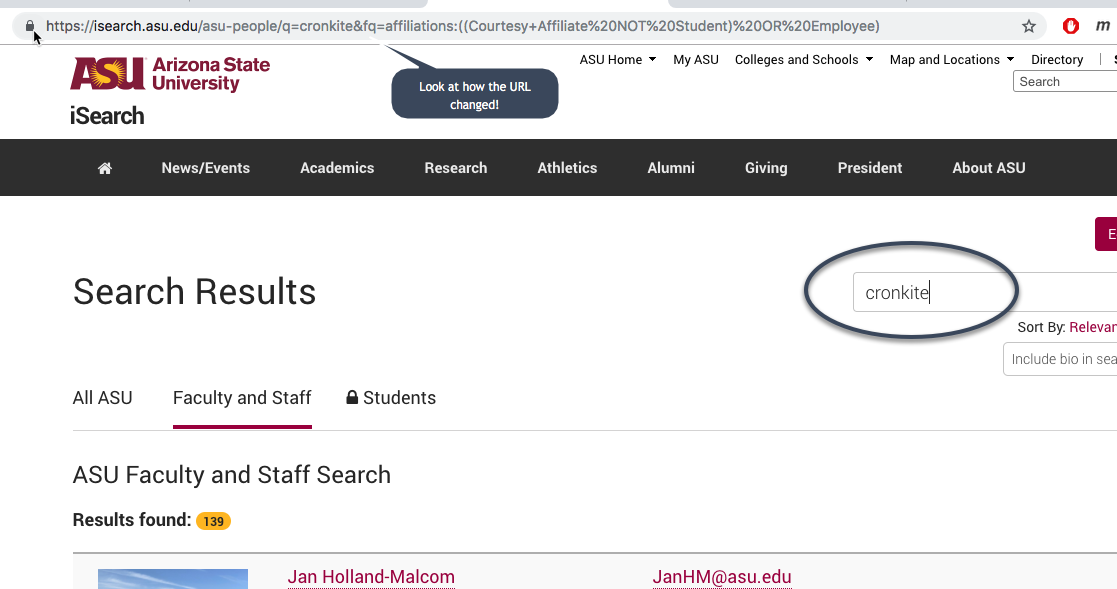

Take a simple example. Go to the ASU website, and look for the directory of faculty and staff. On the search page, type “Cronkite” into the search box. Look at what happened to the back end of the link address, or URL:

When you see

xx=something&yy=somethingelse

you know that there is a query going on inside the site. Depending on which product is being used to build the site, it might have a question mark before the data.

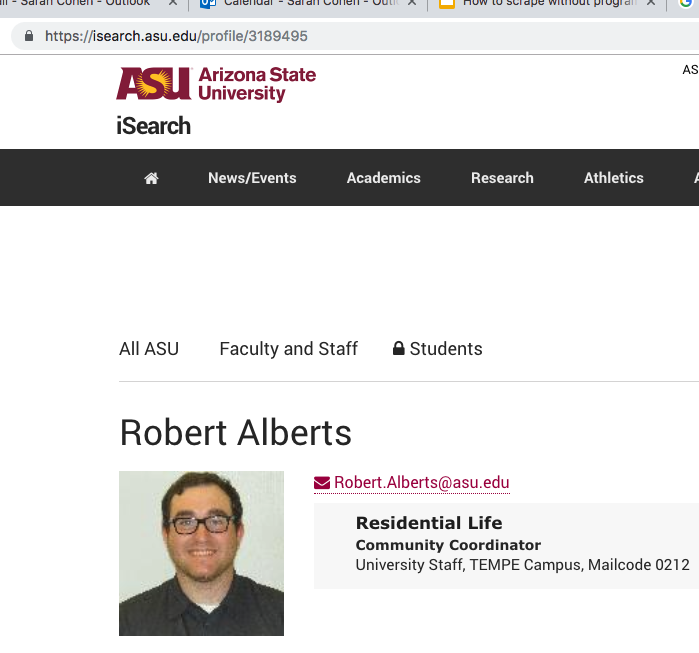

If you search the same site for my name, you should get this URL: https://isearch.asu.edu/profile/3189494. Notice that there is a number at the end This is common: most database programs create unique identifiers for each record, just the way we did in the Excel exercises. That suggests there might be someone with the number 3189495! Indeed, there is:

GET vs. POST

So far, the requests you’ve seen are all GET requests, meaning that the search criteria are built into the URL. There is also something called POST requests, which are usually more complicated and usually can’t be done just by typing into the browser. We’ll get to those later.

Looking under the hood

Using the Chrome Developer Tab (Inspector)

Browsers like Chrome and Safari have built in tools that are designed for developers to test their sites, but can also be used to inspect what is happening on a published site.

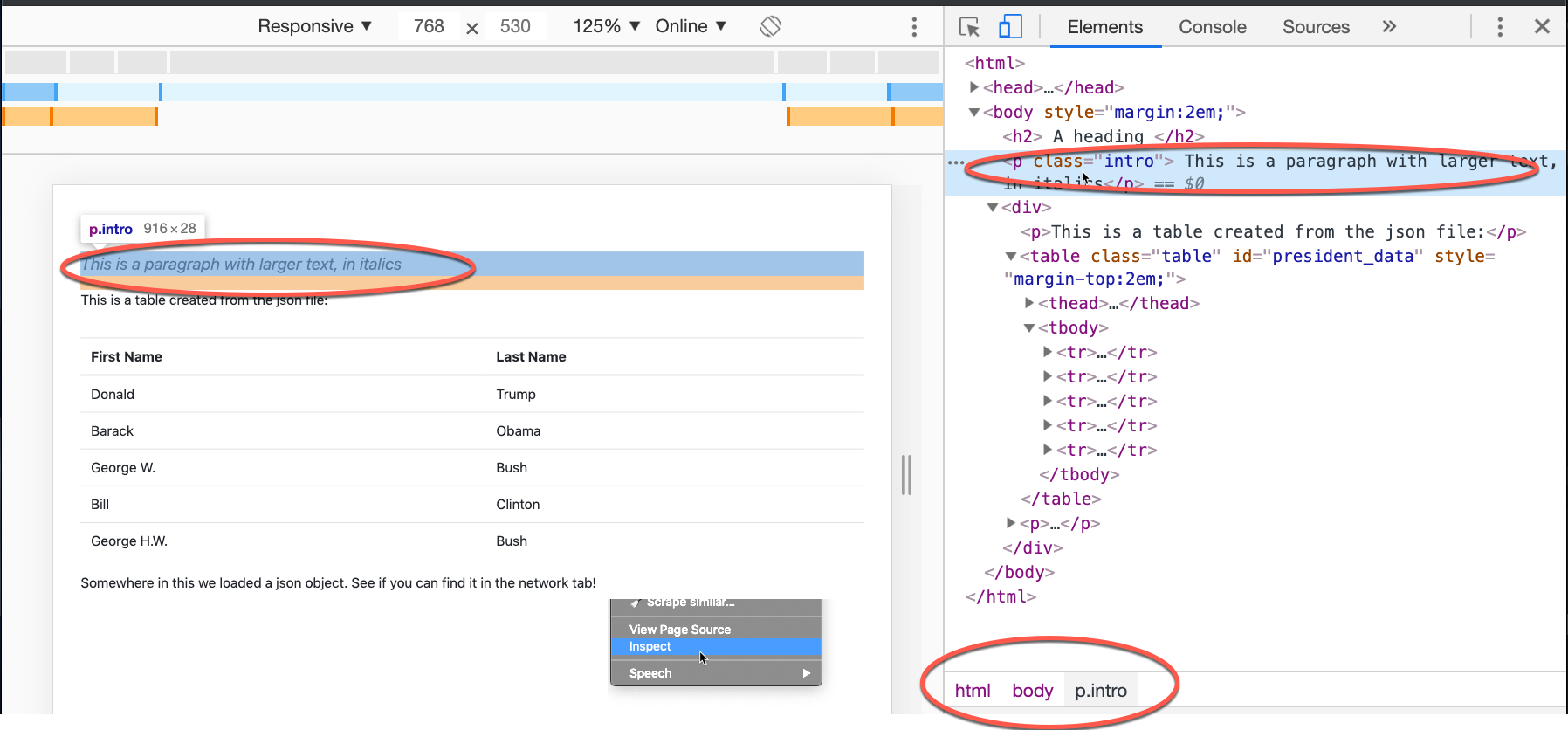

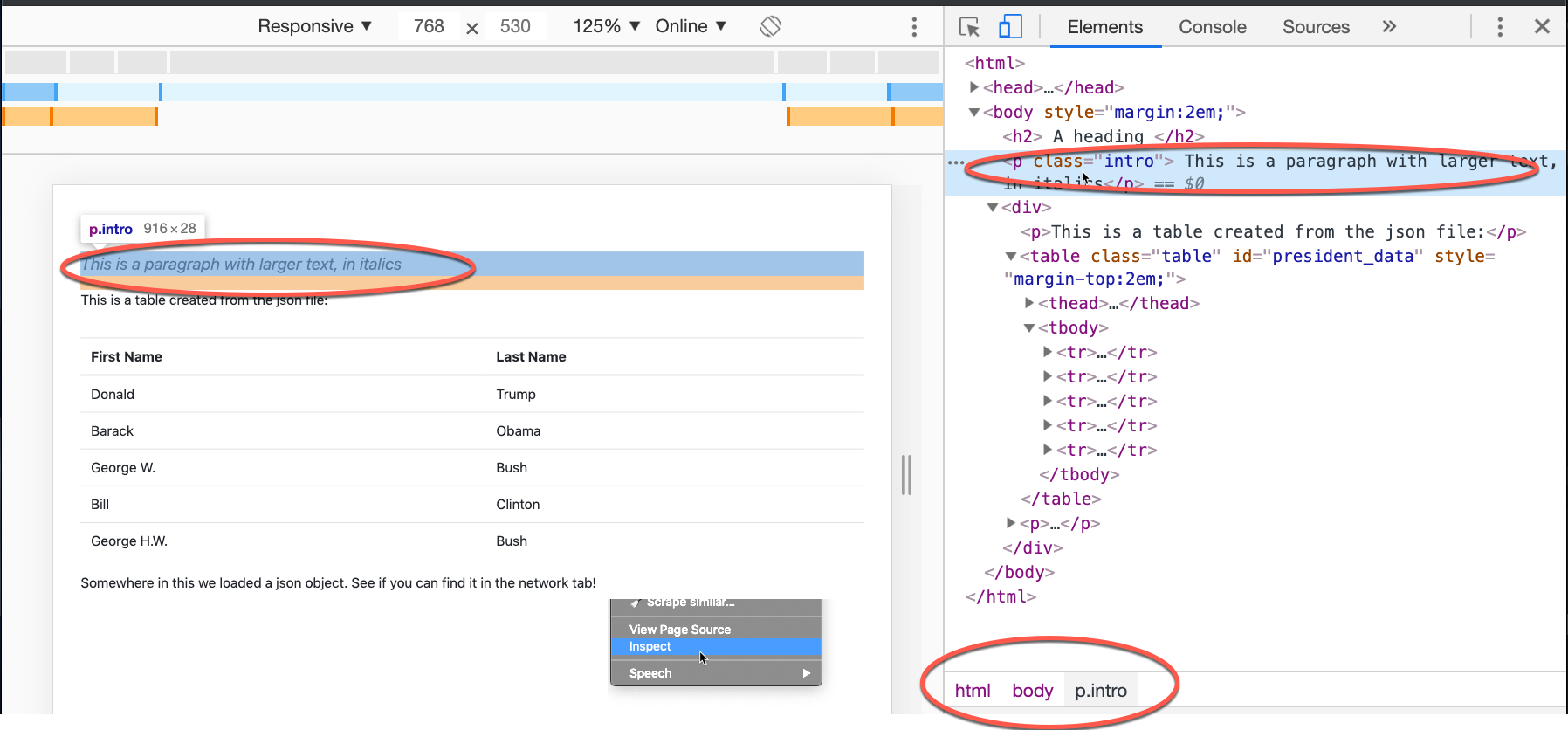

This is an extremely simple web page that has several characteristics:

- In the header, it has several scripts and references to outside resources. Don’t worry about that right now.

- It has a defined style for a paragraph, called p.intro, which will be used later. A style is a way to format web pages using CSS, which you may have learned in high school or in a basic computing class in college.

- I has a heading, two paragraphs and a <div> element that contains a table.

- The table is created using a script from a json file held in the same directory.

Right-click anywhere on the page and choose “Inspect”. It will open to a different part of the page depending on where you click. Expand and collapse the little arrows to show and hide the elements.

Only the “body” tag is opened in this image, but you can see the structure of the page and the tags, id, class and other details of each element. At the bottom, the Inspector tells you the route you’d take to find to the currently selected element on the page. In this case it means, “beginning at the top, go to the <body> tag, then look for a <p> tag that has a class of intro”

Getting used to looking at pages like this helps you understand what is in a web page, but also lets you see things that aren’t displayed on your screen.

An important note

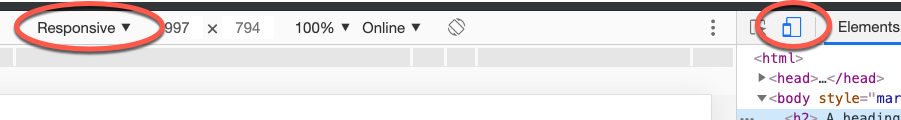

Sometimes you’ll see “Responsive” at the top of the screen when you go into the Inspector. This means that Chrome is testing sites for mobile-friendly responsiveness. If you were building a website, that would be good. But because you’re trying to extract information from a website, it’s bad. Make sure to turn that off by clicking on the image of a phone in your inspector:

Using information under the hood

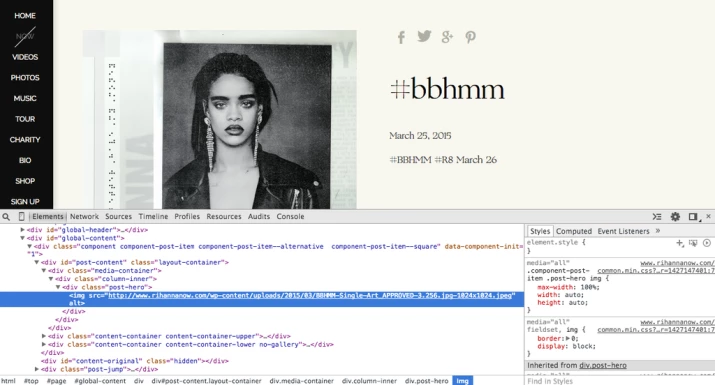

Consider this March 25, 2015 post on Buzzfeed: “Listen to Rihanna’s New Single” describes how Buzzfeed looked behind Rihanna’s website and found a link to a new song that was top secret in the industry and wouldn’t be released for another day.

This is what happened: The author, trolling through the web page, found a link that contained the phrase “APPROVED-3.256” Copying and pasting that link into a browser showed the promo for her hit single.

Griff Palmer, then of The New York Times, helped Declan Walsh prove that the same company was behind a ring of fake universities, identified by working backwards to find links to the same images, accreditation bodies and similar telltale signs. He eventually found more than 350 schools with signs of similarities.

Getting used to reading underneath the slick presentation can reap stories and scoops.

Overriding page limits

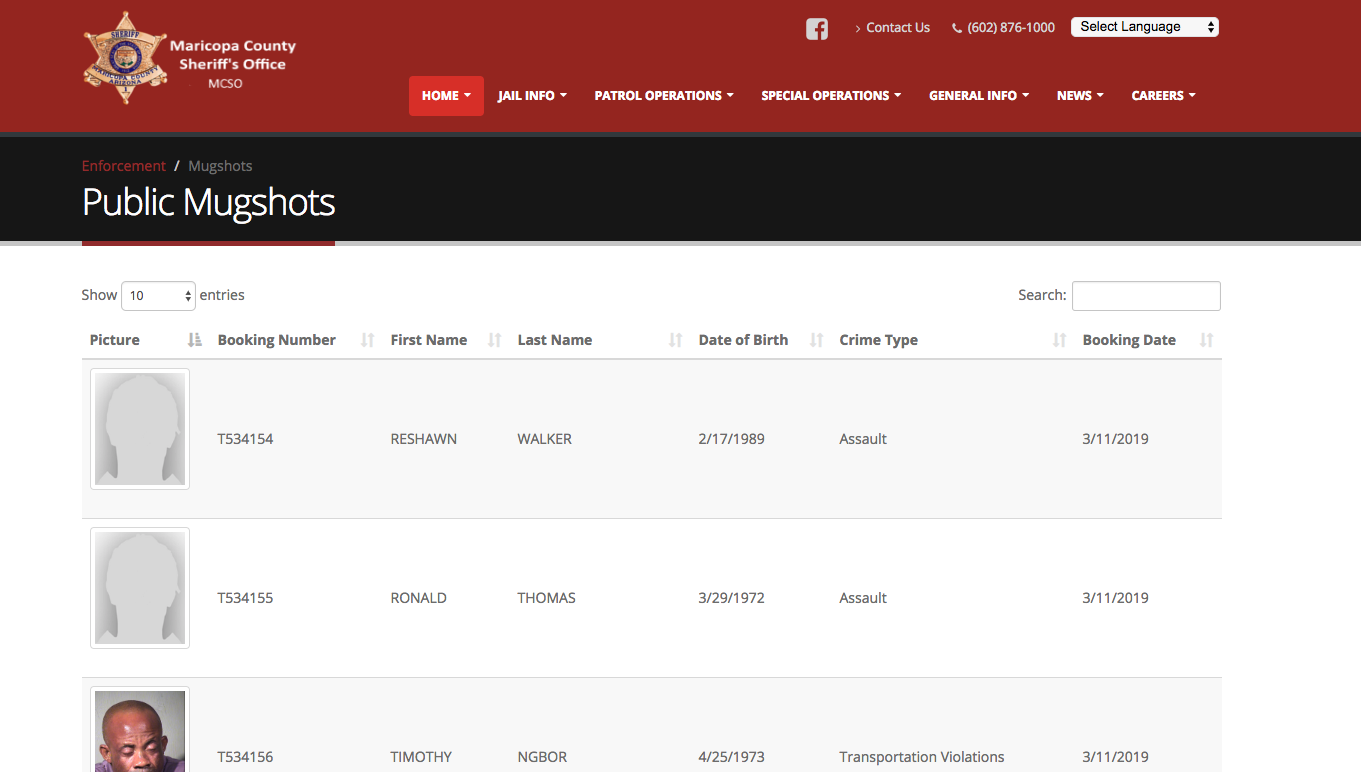

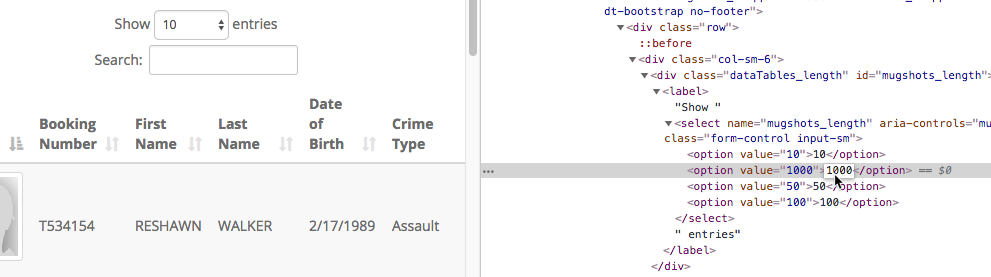

Some websites can be tricked into giving you more at once than you think. One example is the Maricopa County Sheriff’s public mugshot site, which gives you information on the people who are in the county jail every day.

Hover over the box with the “10” in it, and right-click to get the developers’ window by choosing “Inspect”. In your inspector, change one of the options you see from 100 to 1000. (Make sure to change the value=”100” part inside the option tag. That’s the part that the program will pay attention to – the other one is just what you see on the screen.)

When you select it, you should be seeing all of the mugshots for that day.

This doesn’t always work, depending on how the website was created. Sometimes looking at the page source shows more than in the document model, and sometimes all of the data isn’t loaded at the beginning.

One hint is that if you click on “Next page” and there is no hesitation before it shows you the rest of the records, there is probably a dataset sitting on your browser. If it takes a second, it is probably going back to the original server to get more.

The json miracle

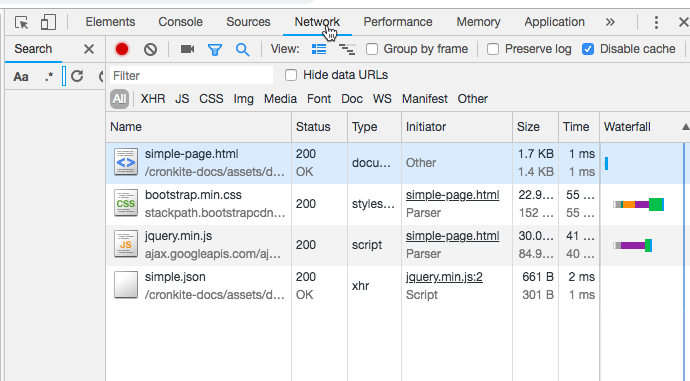

This time, you’ll look at the network resources tab of our simple web page.

- Open the inspector

- Load the page (or refresh it if you didn’t have the Inspector open already)

- And select the Network tab. (You may have to look for little » arrows to find it.)

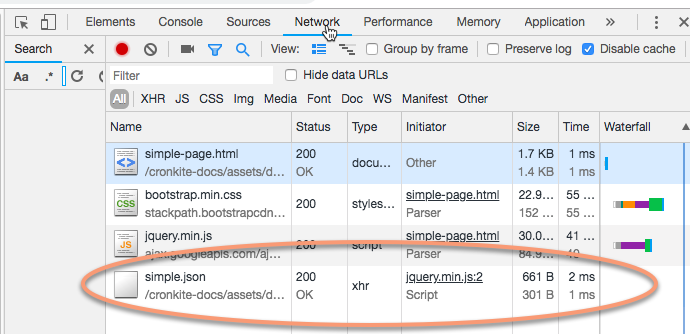

This lists all of the resources that are accessed over a network to build your page. It includes items referenced in the head, and items loaded by scripts elsewhere in the page. Here you can see that it references the original page’s HTML; bootstrap and JQuery resources; and something at the end called simple.json, which is initiated by the JQuery.

Click on the json file, and take a look at what you see. (You may have to expand the little triangles to get to this):

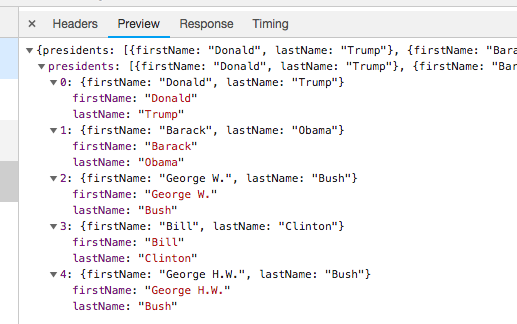

What you have is a json miracle! If you reviewed the tutorial on file types, this is one of the best-of-all-worlds scenarios.

This is a little database that can be converted to a .csv or can be read into R without having to scrape anything! Most websites that use JQuery or similar libraries have a json dataset somewhere buried in them.

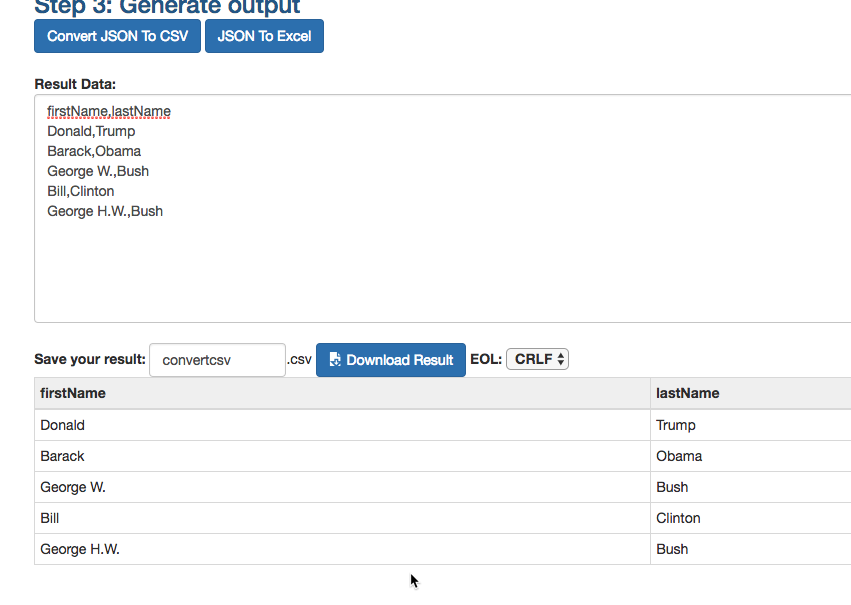

Try right-clicking on the json object on the left side, and choose “Copy” -> “As response”. Now go to a json-to-csv converter (I use this one) and paste into the box. Now you have a csv or Excel file ready to download, with a preview of what it looks like:

A bigger JSON miracle

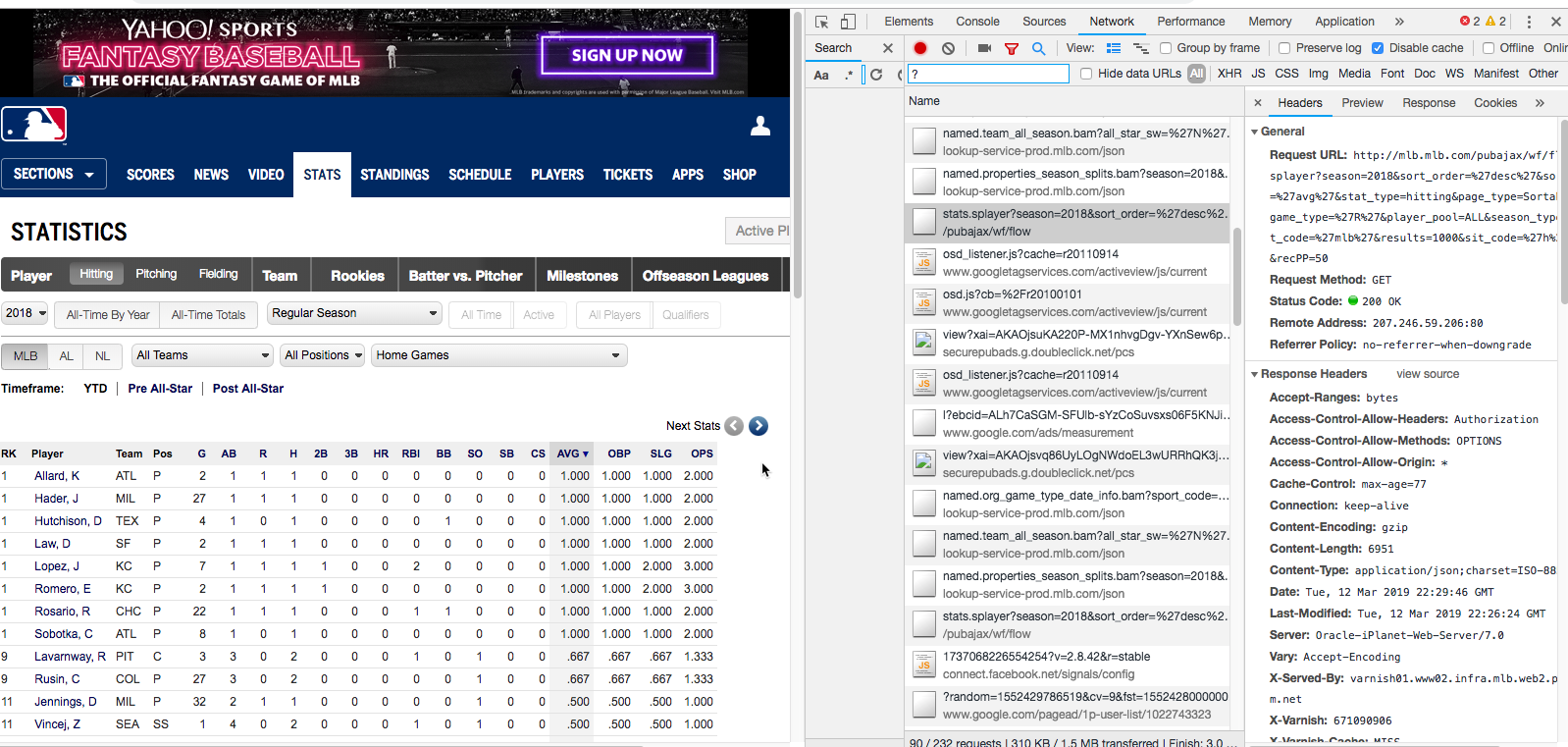

Open your Inspector panel, and go to this list of Major League Baseball player statistics

(Once again, be sure your “Responsive” setting is off by clicking on the little phone in Inspector. Otherwise you’ll be sent to the mobile site, which is different.)

You’re interested in getting to the data shown on the left side of the screen, but you don’t want to have to page 21 times to get it.

In your network tab, somewhere down the side is a file that begins with “stats.splayer?season=….” These are often hard to find, but that is where the JSON file that we looked at earlier resides on this page. (Often, you’ll look for something that has “ajax”, “jsaon”, “xml”, or “xthr” in the name. Other times, just scroll through and look for requests or responses that look like data.)

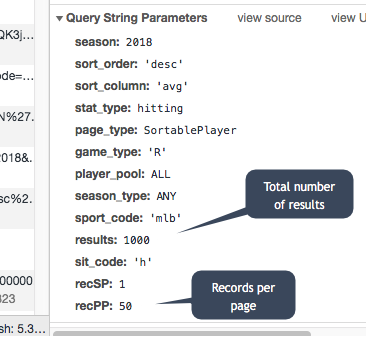

You should see a ver long “Request URL” on the right. If you scroll all the way down, you’ll see that request has been split up into its pieces, which we can see under “Query String Parameters”

Here, we can see what characteristics we need to change to get more of the data at once.

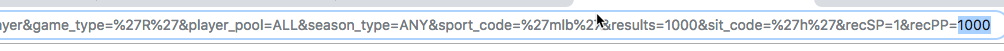

Go back up top, and copy and paste the “Request URL” into a new browser window. This will bring a new page with the first 50 rows of the table. Just go back into the browser’s address, and change the 50 at the end of the URL to 1000:

It will take a little longer to load, but now you’ll have a JSON file with the first 1000 rows (you can see that there were a total of 1033 if you study the first few rows of information. You could change both the total number of records and the records to page to a higher number if you wanted, to get them all.)

Copy and paste the new address into your nifty json to csv converter, and you’ll get a downloadable table ready for analysis.

Scraping with XPATH

There may be no JSON or XML miracle waiting for you. Instead, you might have to convert the HTML inside a page into a spreadsheet or database file.

Samantha Sunne has a terrific tutorial showing you how to do this in Google Sheets. (It’s one of the rare things that Google Sheets can do that is missing in Excel.)

Document object models and XPATH

Think of a web page as a tree - there are two big trunks (the head and the body), then there are little branches that are all from the same trunk. The document object model - or DOM - defines that structure using tags, attributes and element names.

Go back to our simple web page, and open the Chrome developer tool using by right-clicking anywhere on the page and choosing “Inspect”. The current element – the one that you have selected – is shown as a path up that tree. In this case, selected paragraph the third level down:

XPATH is a language that lets you select any of these tags. It starts from the top and moves down until it finds what you’re looking for. In this case, the first <p> tag on the page would simply be referenced this way:

body/p (starting from the top ahdn)

or

//p (the first p it finds anywhere)

Using the Chrome browser, install an extension called Scraper. This is the one you want:

XPATH can get quite complicated because it’s so powerful. For example, say you don’t know which paragraph you’re looking for but you know it’s just after the second H1 heading. Your XPATH command then might be:

/h1[2]/p

A simple scrape: Texas Death Row

The list of inmates on Texas’s Death Row is a very simple list that is easy to scrape.

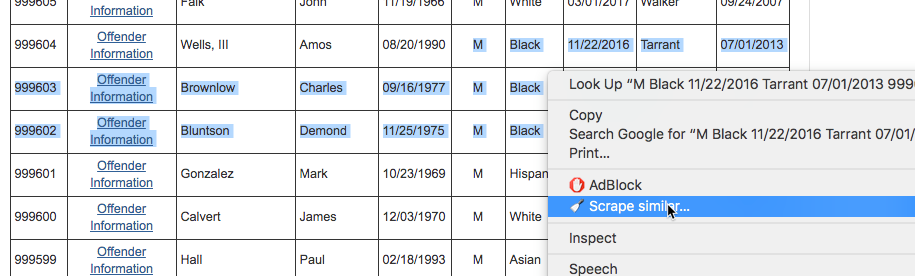

Select some cells in the table, and before you do anything else, look at your inspector. Look at the bottom of the screen, and it will show you the route that had to be taken to get to your selection. it starts with the html tag, goes to body, then a bunch of other tags, and eventually to a “tr” tag.

Now go back to the table, make sure you have a few rows roughly selected, right-click and choose “Scrape similar”

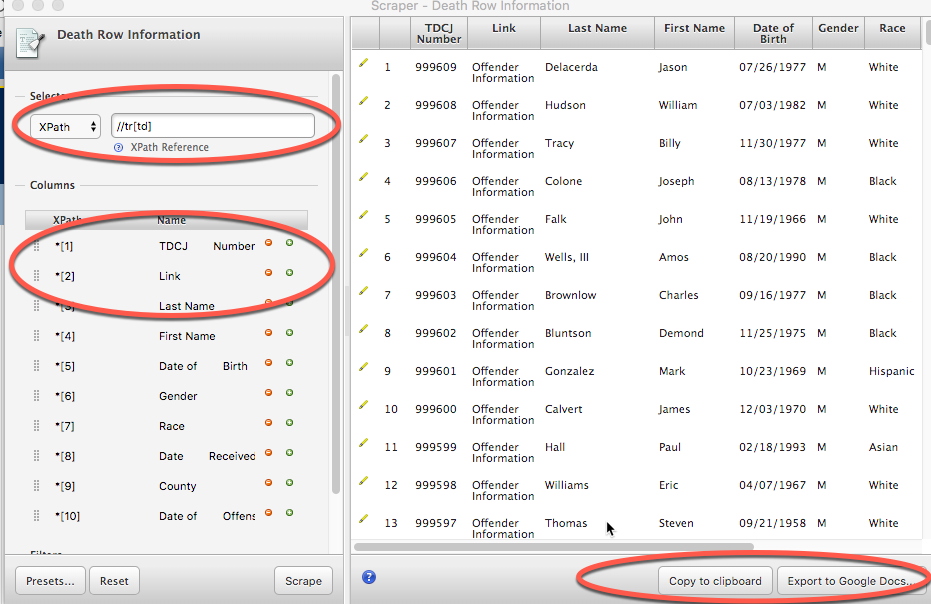

That should bring up a list that looks pretty good – it has the id number, the name, dob, etc. in nice columns and rows, and an invitation to copy to your clipboard or export to google docs. (If you get nothing, check to see if the kind of scrape is XPATH rather than JQuery. If it isn’t close down Chrome and try again. I don’t know how to fix that when it happens.)

Here are the details when it works:

Because this page is so simple, all that the scraper had to do was look for any TR tag (//tr), then it is asking for all of the TD tags below that. In other words, there were no other tables in the page that would confuse it. What if there were? You can use other items in the page to steer XPATH to the right place. For instance, this one could have been:

//div[@class="overflow"]/table/tbody/tr[td]

or

//table[1]/tbody/tr[td]

There is one mistake in this table. That is, the Link only shows the words “Offender Information”. We want the actual link. The reason is XPATH always assumes you want the text shown on the screen, not the underlying information, if you don’t say you want it. Try going into the Link area on left, and make this change:

*[2]

to

*[2]/a/@href

This means that we are looking for the link (an <a href=…> tag) below the table cells. The “a” refers to the tag itself (a link) and the @href refers to an attribute of that tag, or its URL. Anything that is a tag is just shown as is. Anything that’s referenced INSIDE the tag is an attribute, and it’s preceded by an @ symbol.

On your own

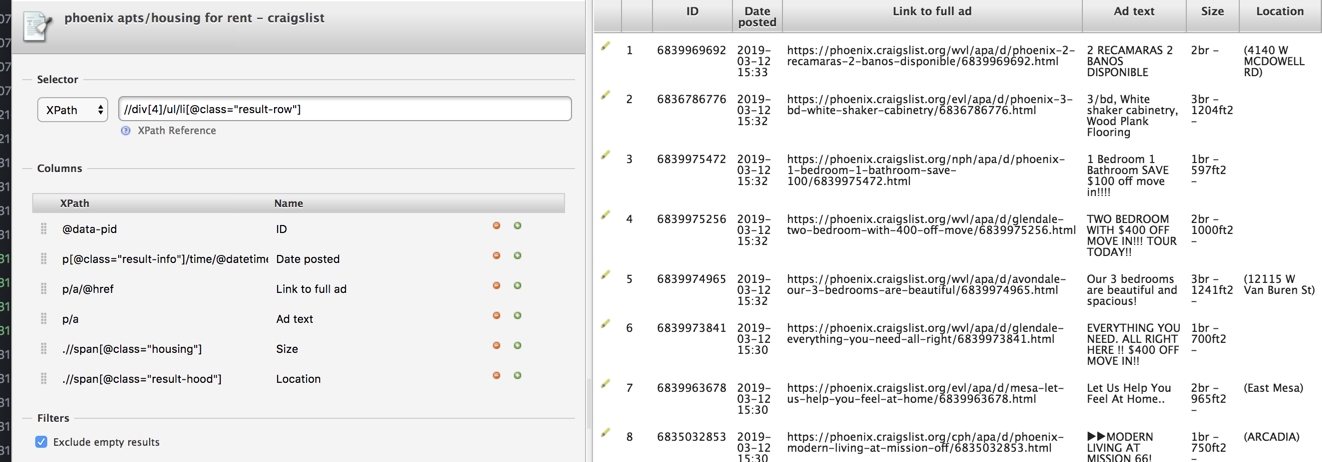

Try scraping Craigslist for your town using the Chrome Scraper. Look at the elements in the Inspector to see what kind of hidden information you can extract. Here’s what I came up with for a list of items that could easily be extracted from a Craigslist listing using the thumbnail view: