Reporting from the outside in

Many reporters approach a long-term project by researching “from the outside in”. This means circling around a topic using publicly available information and people on the fringes of the topic before they approach a key source.

In our case, your goal is to know exactly what you are looking for and what your rights are before you ever contact the agency.

Generally, here is what you need to learn before you request electronic public records:

- The specific agency that holds the records you want to acquire

- How those records are maintained and used.

- The formal name of the form or database that you want.

- Which portions of the records are public under the relevant law.

Taming your topic

Start by thinking of a story idea or a line of coverage that would benefit from some public records held in database form. These aren’t just ideas that you think need some “numbers” – if that’s all you want, then a public information officer or special interest group or expert can probably just give them to you. Instead, think of something that requires individual levels of information or a story that isn’t just dependent on one or two facts.

Example: You want to report on wildfires in Arizona. If you already have a story, you may just want to know how many lives, acres and dollars have been destroyed by wildfires in recent years. This fact is readily available from a variety of sources. But if you want to delve into the details of each fire, including exactly where it started, how it started and how it spread, you are likely to need more granular data: records on each fire.

Get inspired

You should do a thorough search on where you are on this story. Who else has done something similar? Was it a long time ago, or in a different area? What did other local coverage miss?

Sources to check include:

- IRE resource center, story database and story packs. To find stories, be sure to log into IRE using your membership account, and search in the main page search box, not the sidebar:

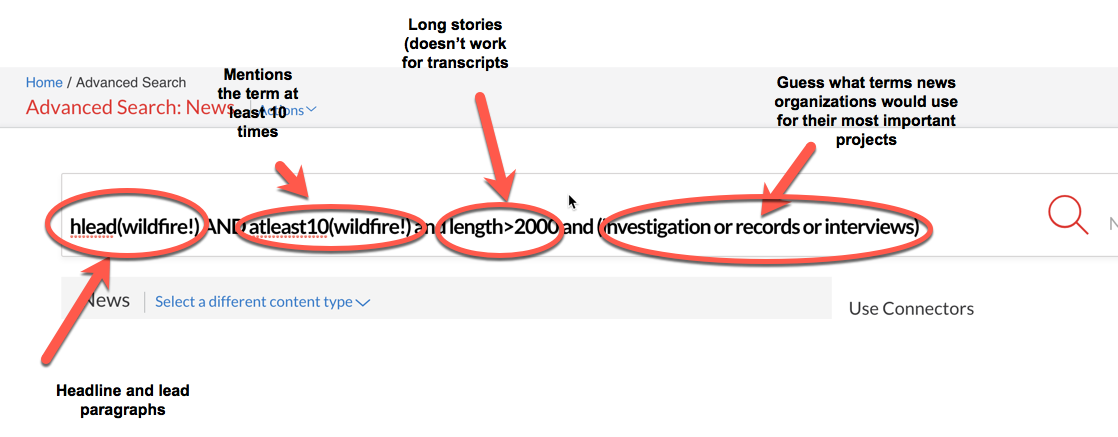

- Do a targeted Nexis or Proquest search through the library, limiting your results to long stories that contain keywords that will limit your results:

-

Do a good Google News and Google search. For example:

intitle:wildfire intext:(wildfire AND investigation AND analysis)

In each of these sources, pay attention not only to what they’ve found, but to the experts they quote, the organizations they mention and the documents or data they source in graphics and in the stories.

Find people who know more than you

Look for:

- Congressional (or state level) legislative testimony

- Inspector general, auditor or other oversight reports (state, local or federal). Federal agencies all have inspector general offices; every state has a State Auditor, who usually works for the legislature. Congress uses the Government Accountability Office, or GAO, to do investigations and audits. Each of these reports will offer names of data systems and records that they used to produce their reports.

- Interest groups that cover your topic. You can use the Encyclopedia of Associations, which is available to students through the ASU library through the library, or look at Project VoteSmart’s special interest group list for national organizations. Then look at their websites to see if this is a topic they care about.

- People who have been involved in the issue. Retired agency employees - especially inspectors - are usually quite knowledgable and are interested in helping the public understand what they used to do.

- Lawyers who represent people hurt by the system you want to examine, or victims themselves.

- Academic researchers who have published about your topic. Use Google Scholar to find them. Be sure to read through any relevant articles they have published before you call them.

- Back to IRE, this time for the Tip Sheets section. (search it the same way you do stories, using the box in the center, not )

In each of these sources, you should focus not on their findings or opinions, but on HOW they do their work, and what documents or data they rely on.

Find other data that has been released

Look on websites of other cities, states and the federal government to find what data might have already been released. Don’t expect it to be complete, but it will give you a least common denominator for a lot of sets of records.

Federal records are often a subset of what’s collected at the state level, which is in turn a subset of what’s collected by counties or cities. As an example, water quality measures are taken one by one by individual water utilities sampling specific households. Those records are often on paper. They are typed into a database, then usually forwarded to a state agency, which standardizes the format at sends them along to the federal EPA. At every stage, some details are lost.

Some places to look:

-

Public records aggregators : data.world, muckrock.org. There may be data aggregators for your specific topic as well.

-

Open records portals in the federal government and some other states and cities. Other places that have released data in the past include California (state), Oakland, New York State, New York City, Washington DC and Chicago. Think of these as the minimum you should be able to get in most areas.

Narrow your topic and your story ideas

Now that you have a little background and can guess how difficult it will be to get records, you’re ready to narrow your story ideas and your plan for acquiring the records. Try to come up with two or three story ideas or questions that you think you’d like to address. In our example on wildfires, we now know that the Arizona Republic did a major expose on fire risk in the US just a couple of years ago. That means the story idea must be a little more targeted and up-to-date. Examples might include:

- Are fires in Arizona becoming larger and more deadly, the way they are elsewhere in the West?

- What have zoning and building codes done to alleviate the risk and danger of fires in the Phoenix area?

- Who fights wildfires in Arizona, and what training and support do they get?

Notice the tense of all of these stories: they are current, not past or future. They also hint at accountability and the need for government action.

Burrowing in on your agencies

Now it’s time to figure out what might be available to you from your own state or local government agency. This involves learning the specific name of the document set or database, and which agency is responsible for it. You’ll also have to research the law to understand what can and cannot be released.

Before you request records, you have to understand:

-

What agency is responsible for them – is it the state or a county? Which department? Which part of the department? You’ll do that by browsing their website, looking at their budgets and searching for any audits or inspector general reports that describe the process. You may also want to call the legislative staff of the committees in the State Legislature that oversee the program that collects the records.

-

What is and isn’t public from those records? This has nothing to do with what is published on their websites, or whether it has personally identifiable information. Don’t just take what they say – instead, study the law and determine if you have a right to some portion of the records.

If you are trying to obtain data rather than individual records, be sure to include specifics in your letter:

- The name of the data system or database that holds the records

- A list of fields (columns or variables) that you are pretty sure are in the data, and that you are sure you have a right to obtain under public records laws.

- If applicable, a list of fields that you acknowledge you are not allowed to obtain, such as Social Security numbers. Only include in this list items that you are absolutely sure the law prohibits the agency from releasing – don’t guess that something is probably excluded from the public record. Let them make that argument.

- Be sure to ask for “all publicly releasable” information and ask them to enumerate any redactions or removals from the data. This puts the burden on the agency to justify anything they are withholding.

- Ask for “any code sheets, lookup tables, record layouts, data dictionaries or other material needed to interpret the data.” You’d be amazed at how often an agency will force a reporter to submit a SECOND public records request just to find out what the codes used in the database mean, or what each column represents. Be sure to get this – you don’t want to have to guess.

- Ask for the data in “any standard data form”, such as plain text files. Be sure to avoid PDF representations of the data. You may not be successful in this, but at least ask for it.

- Offer – no, beg – to talk with the information technology staff to help make the request as easy as possible.