Understanding file formats

When you encounter data in the wild it won’t always come to you in prepared Excel files or Google sheets. In fact, it’s become more common for data providers to post their information in a more universal form that can be more easily read by many different programs, not just spreadsheets.

This should make you happy, not sad. We’re going to skip over the more technical side of the concept of data formats, and just go through what awaits you when you find data on the Web.

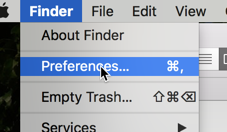

Most file structures are denoted by their file extension, or the part that comes after the period. In both Macs and Windows, you may not see those extensions by default. Make sure you see the extensions on a Mac by opening a Finder window and choosing “Preferences.” Make sure the box that says “Show all filename extensions” is checked:

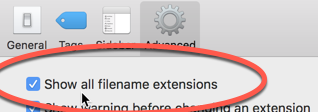

In Windows, use the shortcut for All Settings in the bottom right, then search for File Extensions. A window will pop up and make sure that “Hide extensions for known file types” is unchecked.

tl;dr

Best : csv and other tabular text, json, xml, and any spatial data

So-so : Excel (xlsx), html

Avoid : pdf

Text data

A dataset is considered “text” if it used only to convey characters you can type on a keyboard. Text-based data can be opened and read by a human in any text editor, like Notepad on Windows or TextEdit on a Mac. Most data journalists have a powerful text processor on their computers so they can easily check any file that comes across their desks.

Examples of text data are CSV, or comma-separated values, that are intended to be used as tabular data; and JSON, or javascript object notation, which is used to convey data across the Web. But other types of text data also exist. HTML files are text-based, even though you see fancy page and text formatting, images and videos. Those items are rendered by your browser using instructions built into the text and separate non-text files held elsewhere on the site. Even modern versions of Excel files, with the .xlsx extension, are text based, though they are extremely complicated text that you wouldn’t want to deal with on your own.

The most common non-text, or binary, files that you’ll encounter are PDFs – the form that most reports, forms and formatted documents are exchanged electronically – and some sort of image, sound or video file.

Tabular data

Not all text data is well suited to using as a data source. For example, we saw during the tidy data tutorial, that Excel files can be nearly useless for data analysis even though they’re conveyed through a spreadsheet. On the other end, files like JSON files are intended to be used for data analysis and presentation, even though they look difficult to deal with in the text editor.

Common file formats

CSV, TSV and other delimited data files

Tabular text, the simplest data to read into any program, can come in several structures. The most common is called CSV, or comma-separated values. Your computer probably thinks that a CSV file is supposed to be opened in Excel or, on a Mac, in the built-in Numbers program.

A CSV file suggests that a program wishing to use the data table should use commas to separate the columns. Usually, the data is enclosed by double quotes when it’s possible to have a comma within the field. The first row usually shows the headings in the same form:

name, position, start_date, age_at_start_date

"Trump, Donald", President, 2017-01-20, 70

"Obama, Barack", President, 2009-01-20, 47

If you see a file like this on the Web, you can open it in your browser and safely save it with a .csv extension so that other programs recognize it, but it’s not necessary. You can use it no matter what it’s called.

Some people use TSV instead of CSV, replacing the comma with a TAB key. The reason is that it’s less likely you’ll need to use the quotes, which then reduces some confusion when your data could include quotes. They are much less likely to include TABS.

Benefits

CSV and its cousins are the international language of data. They work with every open source product and every piece of brand-name software.

Traps

Excel and Google sheets quite annoyingly like to think they know what’s in your data, and don’t let you specify the way the fields are read. This means that if it sees a number, it will treat it as a number even if it’s a Zip Code. It will also turn fields that look like dates into dates, even when they shouldn’t. This comes up frequently in two places. In anything related to schools that list the grades that school includes, you’ll often see ‘9-12’ turned into September 12th or September 2012. In some cities, addresses with dashes also get corrupted, turning 12-21 into December 12th. (This is very frequent in Queens, NY) These are very specific problems, but they are impossible to fix if you lose the original CSV file. (This problem isn’t limited to journalists – one study showed that about 80 percent of scientific studies are accompanied by spreadsheets that have turned gene names into dates.)

You can usually just change the extension from .csv to .txt and then you’ll be allowed to specify what you want the program to do.

The other trap is harder to deal with and is treated differently in each program – that’s the problem of unescaped quotes and line endings in long fields. An unescaped quote would look something like this:

Donald "You're fired!" Trump, president, ...

In this case, programs won’t know what to do. Some, like Python, try to be smart – it works fine if there’s o comma directly after the internal quote. Others completely fail. Even worse, different programs expect different “escapes” for internal quotes. In MySQL and some other programs, a backslash tells the program to ignore the upcoming quote. Microsoft products usually want two consecutive ones:

Donald \"You're fired!\" Trump

Donald ""You're fired!"" Trump

This is a common problem when someone has exported the data into a text file from some proprietary format like Excel.

Because CSV and other tabular text data can have these kinds of problems, you should ALWAYS check the number of rows that were imported against the original file – a well documented dataset should tell you how many rows to expect. If you always check the corners of a spreadsheet or the top and bottom of a file, you should be able to see problems. Pay attention to any error messages or unexpectedly empty areas of the imported file. Journalists have created a utility called csvkit (for Macs or in Python) to make these kinds of tests on your original text file. As a last resort, open it in a text editor like Notepad or UEdit and check the number of lines. {.bg-blue-000}

Fixed-width text

This is another form of a universal file format that can be read by anyone, except it splits the fields at specific locations within a row rather than using specific characters. These are a little harder to read, but are common when you get data produced by old computers in government agencies. The bigger disadvantage is that every field has to be the same size. If someone has a long name or title, for example, it will be chopped off in this format. You will usually need a data dictionary or record layout to tell you how to split it apart.

Trump, Donald president 2017-01-20

Obama, Barack president 2009-01-20

Biden, Joe vice president2009-01-20

Washington, Georpresident 1779-04-30

XML and JSON

XML (eXtensible Markup Language) and JSON (Javascript Object Notation) are two other universal ways to share plain text data, but they work in a very different way from the tabular information we see. In both cases, they define a structure and can have multiple pieces of information within a record. They are both tagged, in that each field is named whenever it’s used. At its simplest, XML looks a lot like HTML (below), except it uses field names and characteristics to do its work:

<employees>

<employee sex="M">

<firstName>John</firstName> <lastName>Doe</lastName>

</employee>

<employee sex="F">

<firstName>Anna</firstName> <lastName>Smith</lastName>

</employee>

<employee>

<firstName>Peter</firstName> <lastName>Jones</lastName>

</employee>

</employees>ß

At one time, XML was the official format required by federal agencies for data transfer, so there are a lot of government-generated XML files.

JSON also defines the structure of a dataset by using the names of the fields, but it’s stored in a somewhat more compact structure:

{"employees":[

{ "firstName":"John", "lastName":"Doe", "sex":"M"},

{ "firstName":"Anna", "lastName":"Smith", "sex": "F" },

{ "firstName":"Peter", "lastName":"Jones" }

]}

Leaving out a field simply leaves it blank in the output dataset.

Most Application Programming Interfaces (or APIs) return their data in .json format, which is easily converted into a complex object by javascript, Python or R. JSON was designed for efficiently transferring data to your browser, so it’s usually the most flexible format. Excel doesn’t open json by default, but Google sheets can easily import simple json objects.

For both XML and json, look for online converters to .csv files online. They won’t handle large documents, but they’re perfectly good to convert files with a few hundred items in them.

Benefits

No one has to guess what anything means in these tagged structures. They can include anything you want, including full documents within one field. Once a computer program can read one of these formats, there are very few ways they can go wrong.

Most computer languages such as R or Python have standard methods of reading these files, making them relatively easy to work with. Don’t curse these formats. They’re your friends.

Traps

They’re often NOT properly created, leading to frustrating “malformed” errors in programs that can read them. Complicated structures – ones with nested pieces of information, such as a list of nicknames for each of these employees – and very large files are almost impossible to open in software without reading it through a program first.

HTML

At its core, HTML is a structured document containing text. Images, sound, videos and other files are linked to them; the formatting you see is done through text instructions. That doesn’t mean it’s easy to work with as a data source. You’ll have to parse the document to get its pieces out.

Traps

Parsing HTML files has gotten easier, but it remains a time-consuming chore the first time you encounter the need. Most of the time, HTML is used when you scrape websites.

Even when you do get the text out, there are often weird entities that are used for things like accents and other characters. For example, instead of a dash, “–”, you’ll see “—” or instead of an “&”, you see “&”. This is particularly annoying in lists of names with accents and other non-standard characters. Converting between the various text encodings can also be a headache, but it’s getting easier. (Old versions of Python choke on UTF-8 characters, like accents or smart quotes.)

Proprietary file formats

Most software saves files in special formats that they and only they can read. Some are so common, though, that there are converters and importers, or they have become de facto standards.

Excel, Access and their cousins

These are files the files created by software that contain special instructions in computer code that are intended to be read by the originating programs. Many of the formats you’ll see originated with Microsoft: .xlsx, .accdb, .docx and .pptx. In fact, Google docs downloads, by default, are converted into these Microsoft formats. Recent versions use a form of XML that contain detailed instructions on formatting, formulas, pages, and other Excel features. Don’t try to use them as text files. Every data system has a way to read Excel files. Some, like Google Sheets, reads them without any special instructions. Programming languages like R have importers.

Benefits

Excel files, when properly formed into tidy data, are among the easiest for sources to produce. They make PIO’s happy because they can be read by human beings using the programs that are on their desks already. They can also contain extra information, like a page of documentation or summaries and charts. Reading them into other programs is often seamless.

Microsoft Access files are becoming less frequent, but it is a format that was used for many years by government agencies to transmit larger, more complicated, databases. They are much more likely to be “tidy” because they are designed to work with well formed data.

Traps

First, Microsoft doesn’t make a version of Access for Macs, which makes it more difficult to import – you’ll have to find a program or utility to convert them into something more universal.

Excel can actually be a problem as well, which is why we advise reporters to request the data in a “plain text”, or CSV, format. If the data conveyed in the spreadsheet isn’t “tidy” it won’t do you much good. Text forms are much less likely to be presented as reports. One common issue is that a column contains different data types – other programs won’t know what to do with them.

I’ve saved PDF because it’s the bane of most data journalists’ existence. PDF files were designed to present information on a page exactly as the person who created it wanted. It’s really a report, not a dataset. But many government agencies now try to pawn off PDFs as data. There are all kinds of issues with PDFs, but for now just leave it this way: You don’t want them.

This list suggests that, depending on the complexity of the data you are requesting, you’ll usually want one of the standard text-based formats: csv or tsv for simple data; xml or json for complicated data.

Spatial data

“Spatial data” is the technical term for data formats that come with information needed to create maps. The important thing to know is that whenever you are offered spatial data, or map files, take them. You can always extract tabular data from them, and they have a lot of other information that is usually very difficult to get. The most common file types are shapefiles (a bundle of files but .shp is the main extension), KML and GeoJSON, a special form of JSON files with instructions for drawing shapes.

Traps

The only problem with spatial data is that sometimes the person doesn’t give you what you need to know. My first mapping project went quite smoothly – as long as I put everything in Greenland instead of Maryland.