26 Scraping without programming

This book will introduce scraping websites in three sections.

This section contains the vocabulary you need and strategies to avoid scraping altogether by finding data already on your computer and using Google Sheets for simple lists.

The next chapter reviews how t o pick apart a page using the R library rvest, which is used to parse web pages.

The last chapter shows you how to programmatically walk through a lot of pages to recompile a more detailed or larger dataset.

26.1 Where reporters get data

Reporters can get data from people, using FOIA, asking nicely or by finding a whistleblower to leak it. But we often also get data from publicly published sources, usually on the web.

There are three ways to get data from the web:

Download it, or use an API1. In these cases, the makers of the data have specifically offered it up for your use in a useful format. We’ll cover API’s later, but don’t forget to study the site for a download link or option. If there isn’t one on a government site, you might call the agency and ask that they add one. They might just do it. We’ve been using downloadable data throughout this book.

Find it on your browser. Often the person making the website delivers structured data to your browser as a convenience. It’s easier for them to make interactive items on their page by using data they’ve already delivered in visualizations and tables. It also reduces the loads on their servers. These are usually in JSON format. You might be able to find it right on your computer. It’s a miracle!

Scrape it. This set of chapters goes over how to scrape content that is delivered in HTML form – a web page. There would be other methods to scrape PDFs, which can be easy or hard.

26.2 A json miracle walkthrough

This walkthrough shows you how to find some json in your browser. Use the Chrome browser for this - Firefox and Safari also have similar features, but they look different.

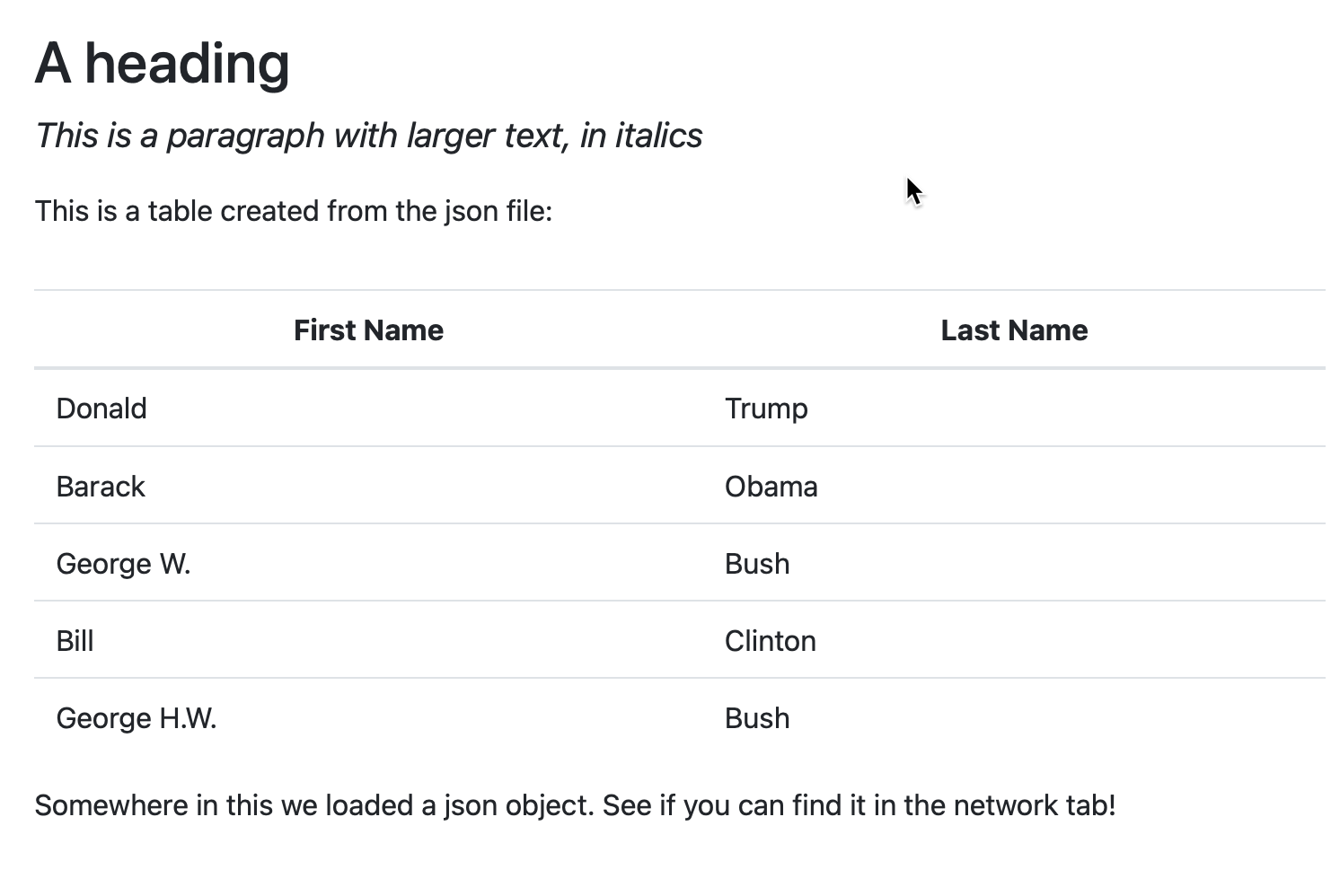

Here is a simple page that will show you what the json looks like and how to extract it. This is what a human sees:

The table of presidents is actually produced using a small javascript program inside the HTML that walks through each item and lists it as a row.

Open the page in Chrome, then right-click anywhere on the page and choose “Inspect”. It may appear as just two items - the “head” and the “body”. But notice the little arrows - they show you that there is more content underneath. For now, we’ll ignore this, but it will be important later.

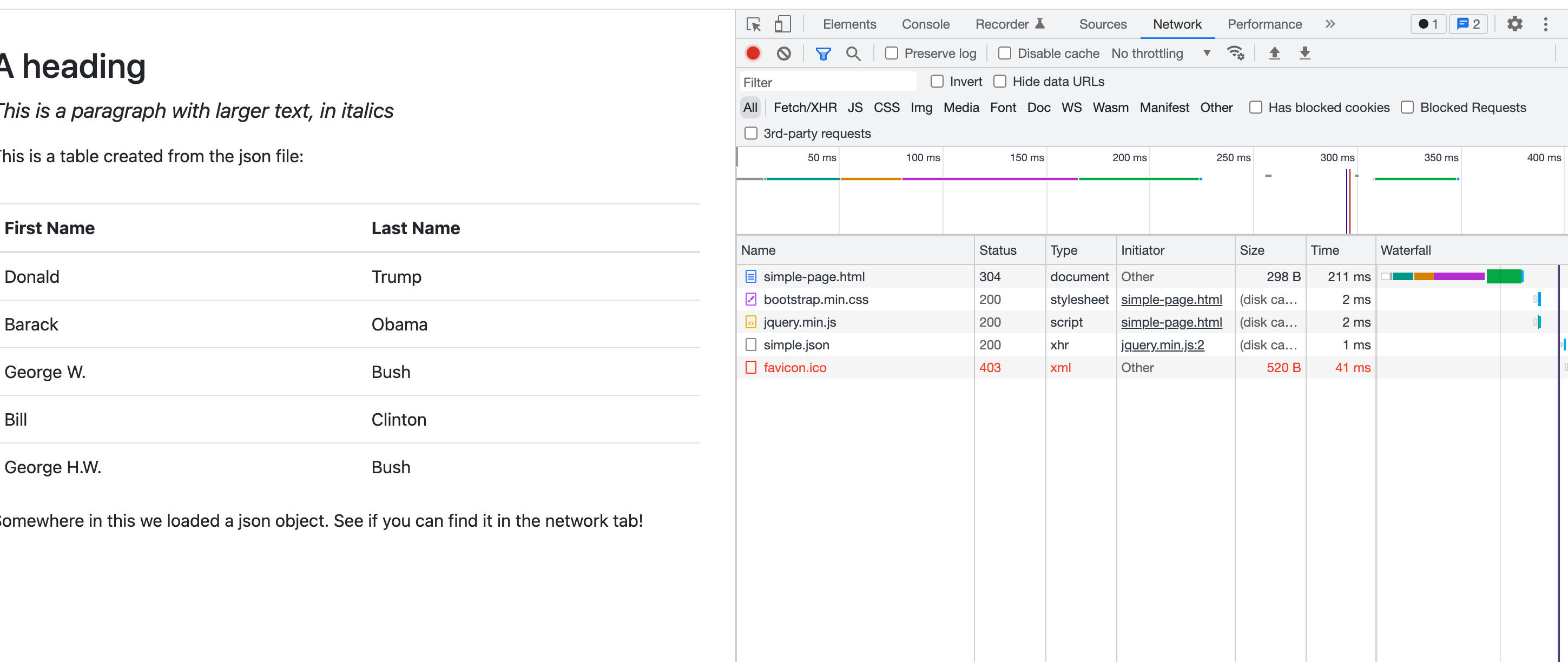

Choose the Network tab, then re-load the page.

This shows you everything that the browser is attempting to load into your browser. (You may not see the “favicon” item. I have no idea why it’s showing up on mine - it’s not been requested!)

You can ignore most of this. Importantly, the “simple-page.html” is the actual page, and the “simple.json” is the data! Click on the simple.json row, then choose the “Response” tab:

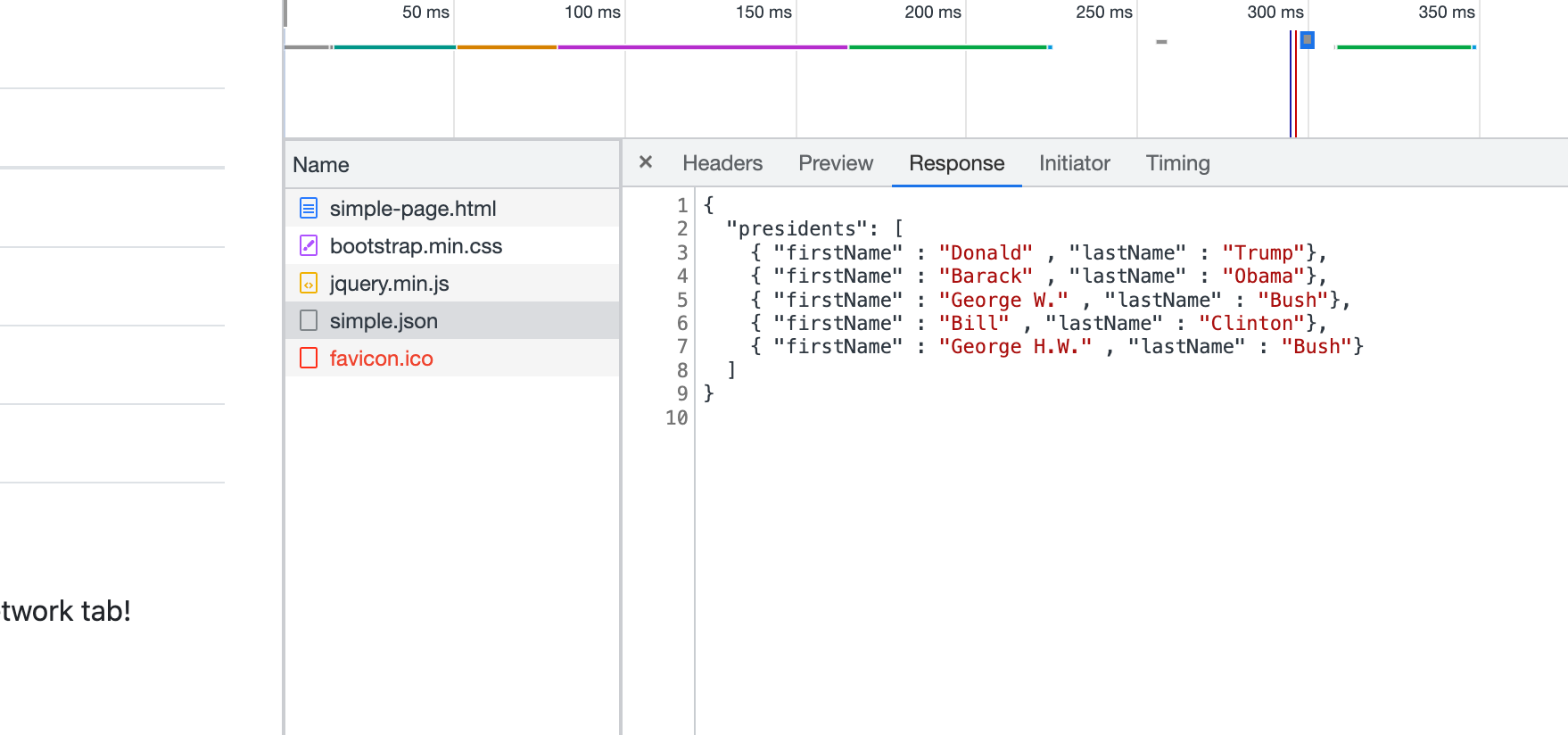

That’s what json looks like - a list of rows within an item called “presidents”, each identified by the name of the column they’ll become.2

Right-click on the simple.json file name, and you’ll see a lot of options. Choose the one that says Copy->Copy link address.

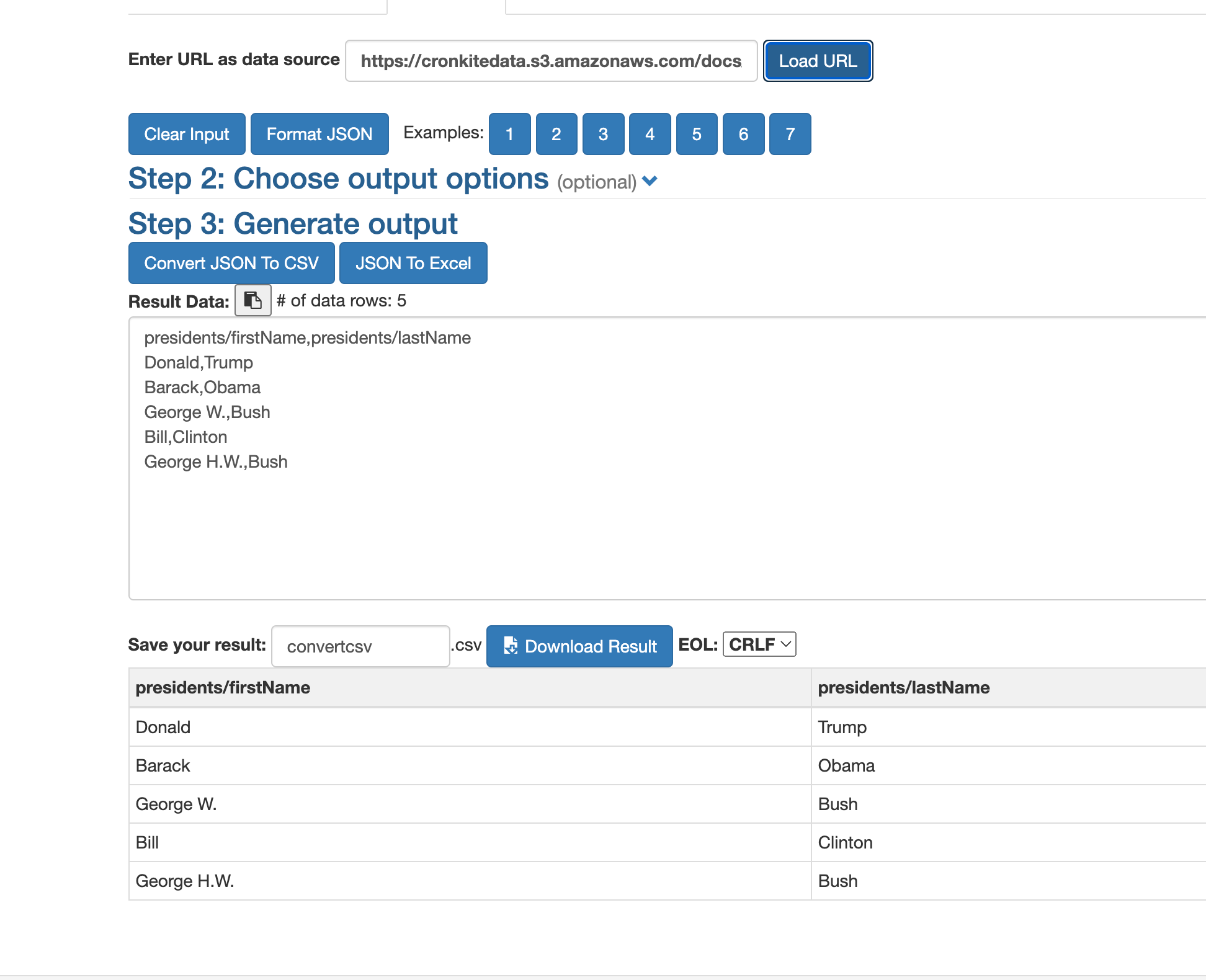

Go to a new browser window and search for “json to csv”. This one is one that I often see first.

Paste your copied link in the tab that says, “Enter URL” and press “Load URL”. You’ll see an option to copy the result as a csv file!

A harder example

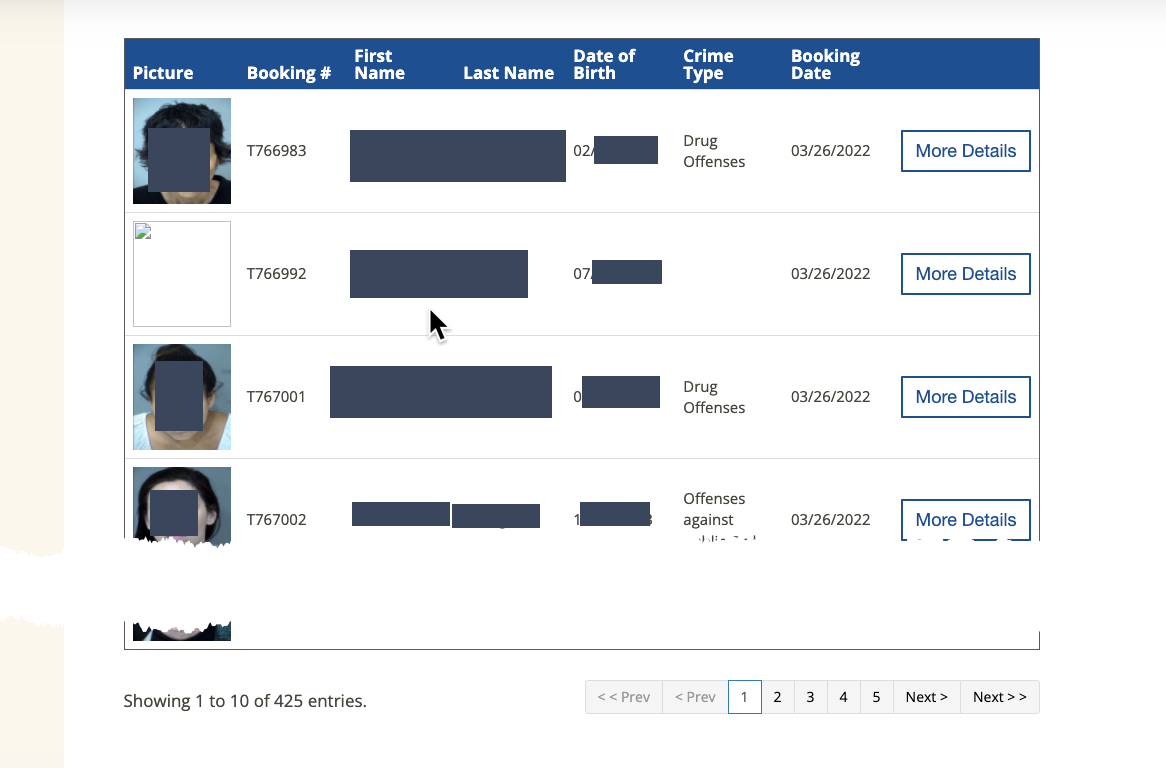

That was easy! But it’s also trivial. However, this method can often save you from having to page through results of a page. One example is the Maricopa County nightly list of mugshots, which may have several hundred new entries each day. Here’s what today’s looked like on a desktop browser (it looks different on a smaller screen).3:

It looks like you’d have to go through each of the five pages to get all of the names of people who were booked into jail that night, but often a json file contains all of them – they’re just showing you one page at a time.

- This page won’t let you right-click to get the inspector. Instead, on a Mac, press

Opt-Cmd-Cto open the inspector window. (I think it’s Shft-Ctl-C on Windows, but I’m not sure.)

This looks like a mess! Don’t worry. Switch to the Network tab, and re-load the page. This time, there are dozens of different things that get loaded on your page, and none of them are obviously json. You have a few strategies to find it.

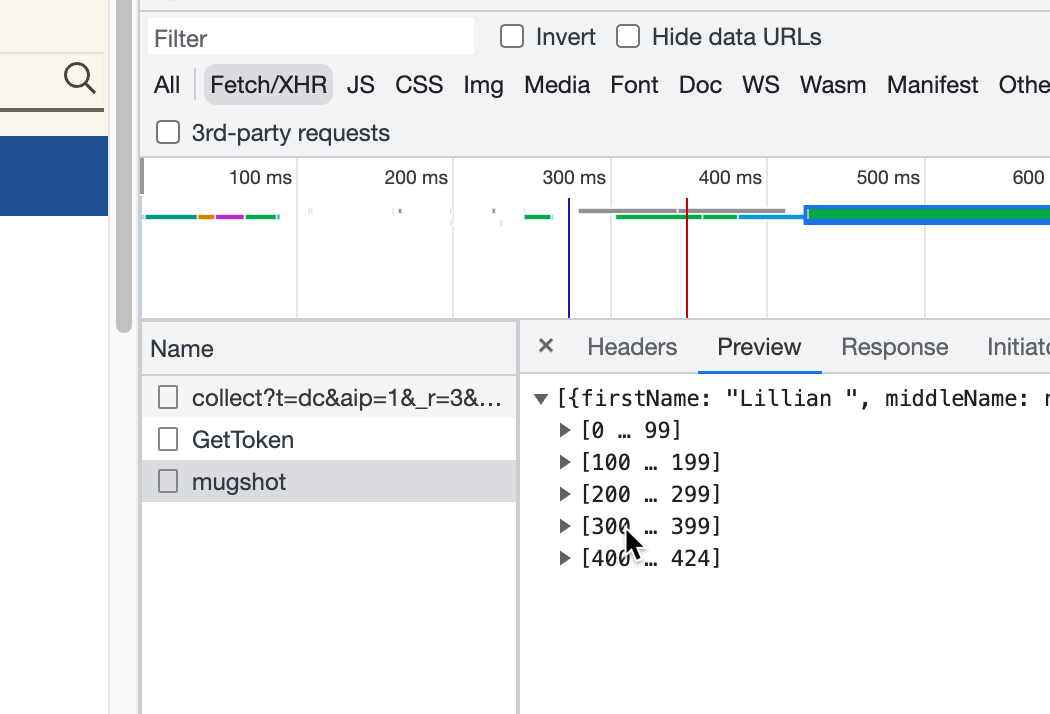

- Press the “Fetch/XHR” tab to see if it shows up there. Use the “Preview” tab to look at what each of them is, and, miracle of miracles, it’s the third one on the list! Even better, it has all 425 entries! (It looks like they’re split into groups of 100, but they really aren’t.)

- Right-click on the name of the file, and choose Copy->Copy link, and repeat the process above to convert it to a CSV file.

In 2022, the county began limiting the number of results to some random list of 300. It appears that searching for an inmate only checks those first 300 results. (It could have been a coincidence that there were exactly 300 inmate on Jan 3, 2023, but I doubt it.)

An even harder example

The New York Times maintains a map with the vaccination rates for various demographic groups by county on its website. At first, the Times didn’t provide a Github repo for the data. How can we extract the data from this map?

The easiest way would be to see if it contains a json miracle!

- Open your inspector panel

- Copy and paste the link to the map page, and open it in your Chrome browser with the inpsectors showing.

- Switch to the network tab. (If you opened the map before opening the inspector, reload it now. )

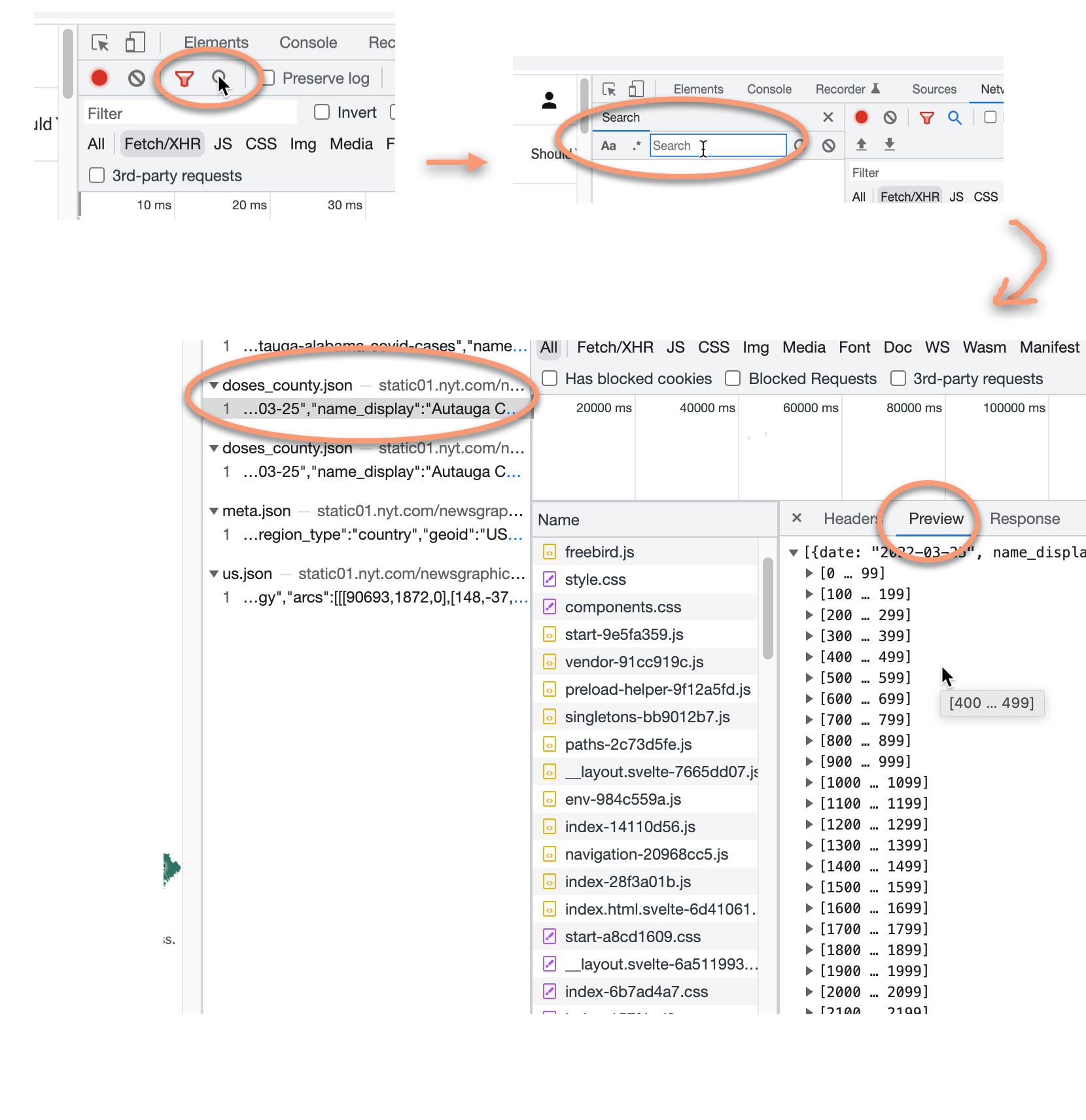

Yikes! The “Fetch /XHR” button doesn’t help us much here. There are too many different json files to check. We could look one by one and see if they’re right, but sometimes that’s just too hard. Instead,

- Open the “Search” button on your inspector (it’s different from the Filter), and type in a county name (this one is “Maricopa”). You should see only a few of them. The most promising is the “doses_county.json”, so try that one first:

This time, it’s hard to find the item in the list of files in the browser. Instead, right-click in the “Preview” area, and copy the object. You can paste that into the box in the JSON to csv converter instead of entering a URL.

26.3 No json? No problem (maybe)

You may not be able to find a json file – either it’s too hard to find, or it’s not useful, or it doesn’t exist. For a simple page, there’s no problem getting the data in Google Sheets. (This is one area where Excel lags behind Google Sheets.) We’ll go into HTML tags in more depth in the next chapter, but if your data is held in a table or structured list, you can import it directly into Google sheets.

Note that this trick is really only useful if your page doesn’t change a lot, or if you just want a one-time snapshot. It doesn’t automatically update, and I don’t know how to capture changes – it would involve a Google scripting program, which I don’t know how to do. I’ve never learned because I usually only gather data for my own use, and it’s easier to program it than to finagle Google Sheets.

The trick to using Google Sheets is to find a table tag (<table>) or a list tag (<ul> or <ol>) that contains the data you want.

Here’s an example, taken from a previous year’s MAIJ cohort: Reporters wanted to know whether Scottsdale was relatively unique in its city council structure, which has no districts. All members are at-large. Some research suggests that this disempowers non-white or less wealthy areas, because more privileged residents are often more active in local politics.

The reporters knew it was rare, but one question nagged at them: Was Scottsdale the largest city in the nation with a purely at-large council? That would make a nice tidbit for the story, but it wasn’t worth a major data collection endeavor.

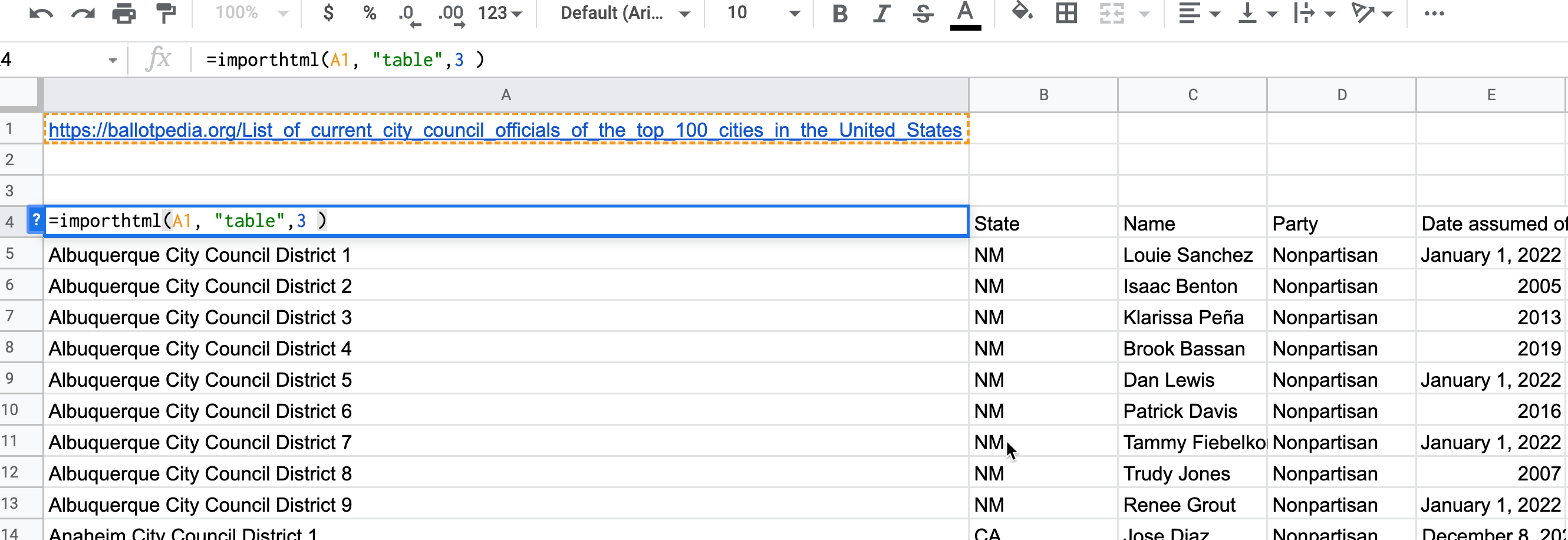

Ballotpedia, a crowdsourced website with information on local governments, had collected a page of city council officials in the 100 largest cities in the US. Extracting this information into a structured table, then using regular expressions, could help make that a relatively simple job. This could even be done in Google Sheets, which also has a regular expression implementation. Because it’s so rare, just getting a list of cities that had no district or ward membership would give them a place to start looking up populations.

This information is stored in an HTML table, identified by the “” element.

- Right-click on the page, and open your inspector. It looks like a mess, but you can search for tables using a simple “Find” using Cmd (or Ctl) -F.

You may notice it says you can find by string, selector or XPath.

In the box, enter “<table” (with the opening “<”, but no closing one.). You should see “1 of 12” in the result box. As you go through the list, the currently selected table will be highlighted. When you hit “3 of 12”, you’ll notice that the browser has selected the table you want. That’s the information we need.

Open a Google Sheet, and copy the page URL to cell A1. This just makes it easier to construct the formula to extract the table.

In cell A3, enter the following formula:

=ImportHTML(A1, "table", 3)That means, “Go to the web address listed in cell A1, look for”table” tags, then return whatever is in the third one.”

When you hit “enter” the whole table will populate on your Google Sheet. Unfortunately, you can’t get the link to the city from this method, which means you don’t have a good way to extract a city name. We’ll come back to this when we go to scraping in R. (There is a way to get this in Google Sheets, but it’s not very reliable – it will choke as soon as it encounters a missing URL.)

But if you just need the text of a table or list in a spreadsheet, this is an easy way to get it. (To get a list from an “ol” or “ul” (ordered and unordered lists) tag, use “list” instead of “table”.)

26.4 Recap

Sometimes – especially on modern websites that create interactive elements on the fly – the data you need is already sitting on your computer. In fact, it’s quite hard to scrape those in other ways because the HTML is created when it’s loaded into your browser.

But when it’s not, there may be another simple way to get the content.

The problem is that getting the content without programming can leave you unsatisfied because you can only get the text, not any of the underlying information. The next chapter shows you one method of getting more information from a web page using CSS selectors.

I sometimes use a Chrome extension called “Chrome Scraper” to get slightly more complex information out of a website, which uses a language called XPath to parse a web page. It’s harder than the CSS selector method, though, so I’m skipping it for now.

“application programming interface”↩︎

In R, our style was to name columns in lower case with words separated by underscores. In Javascript, the custom is usually called “camel case”, with words smushed together and the first letter of each upper cased. It’s just a custom, not a rule.↩︎

I’m hiding names of people to the extent possible, and won’t list them in text here - they’ll only be in the images. Instead, I’ll show pictures of how to find the json when a name is necessary. Although this book is probably not indexed by Google, it’s possible that it could be some day, and I don’t want their names to show up in a Google search.↩︎