23 Inexact matching and regular expressions in R

In this chapter

- Resources for using regular expressions in R

str_detect()in filters- Dealing with upper and lower case

str_detect()in creating a new category in mutate- Negating a match – everything EXCEPT.

str_extract()to get the value that was foundstr_replace()andstr_replace_all()to clean columns- A note on “list” columns

Now that you’ve looked at the general idea of regular expressions, this chapter is a brief overview of how they are implemented in the tidyverse.

The key functions of inexact matching that you’ll use all take the same general form. Instead of a direct operator, such as mycolumn < 100 , the are implemented in functions.

We’ve already looked at the function str_like(), which allows for upper or lower case with wild cards. This chapter, however, use the regular expressions that were described in the last section.

23.1 Resouces for using regular expressions in R

The tidyverse cheat sheet on the package

stringr(which is party of tidyverse) has the outlines of each function that uses these regular expression. It’s a little hard to read, but has all of the shortcuts on the second page. Look at the part that says, “type this”, which translates to “to mean this” as in Regex101.Nathan Collins, a student in the 2022 MAIJ cohort, [did an explainer on using

str_detect()on the ACLED])(https://npcdata.github.io/projects/collins_explainer.html) data that many of you are using for your projects

In R, regular expressions are a little different than in the Python and other languages listed in regex101 .

The expressions are still case sensitive! In real life, it’s often easier to use a combination of functions, first to turn the column into lower case, and then to use the regular expression on that. It’s much easier than trying to match which case it is.

Instead of one

\backslash (\), there are two (\\) to “escape” special characters like parentheses or to use a special type of character such as a digit.

23.2 Sample data

For this example, we’ll use a small set of Tweets from Donald Trump, representing the last few months he was on on the platform. It runs from Nov. 1, 2020 to Jan. 8, 2021, when Twitter banned him. Retweets were removed, but there are a number of tweets that are just links to other content.

Here is a random sample of the 1,112 tweets:

Using tweets as a source for data is a little dated, but it’s a good example of trying to pick out text from a set of short items.

String functions for regular expressions

str_detect( col_name, expression)looks for the presence of the expression, and returnsTRUEorFALSE.str_extract(col_name, expression)does the same thing, except it returns whatever the first thing that matched your expression. It includes wild cards, so it could just return the whole phrase.str_match(col_name, expression)is more complicated - it lets you use pieces of the expression, but it returns a list, which is hard to work with. We’ll skip that for now.

Some other useful string functions are:

- To convert the case, use str_to_lower(colname), str_to_upper(colname), or str_to_title()

- To smush together phrases, use str_c() or paste() or paste0.

Convert everything to lowercase

One strategy for using regular expressions is to convert everything to lower case before trying to match text. In R, the regular expression is, by default, case-sensitive and it’s difficult to predict how it might show up in free text like this. 1

trump_tweets <-

trump_tweets |>

mutate ( tweet_lowercase = str_to_lower(text))23.3 Using str_detect

The function str_detect() results in either TRUE or FALSE. It’s very useful in two situations:

- As a filter for rows in your data.

- As a way to assign values in an

if_else()orcase_when()expression, when creating a new column usingmutate().

Example 1: Filter for “biden”

trump_tweets |>

select ( tweet_date, tweet_lowercase) |>

filter ( str_detect ( tweet_lowercase, "biden"))But that leaves out any time he’s called “sleepy joe”. Instead, look for either “sleepy joe” or “joe biden”:

trump_tweets |>

select ( tweet_lowercase) |>

filter ( str_detect ( tweet_lowercase, "(biden|sleepy joe)")) Now, use either the reactable() or the DT() library to make a table that will show you the entire text:

trump_tweets |>

select ( tweet_lowercase) |>

filter ( str_detect ( tweet_lowercase, "(biden|sleepy joe)")) |>

reactable( striped=TRUE,

searchable=TRUE) (When you have multi-word phrases, be sure to put the whole thing in parentheses. Otherwise, it doesn’t know how to interpret it: It could be (biden|sleepy) joe, which wouldn’t match much! )

Keywords

Another way to look at these tweets is to look for signs of populism – words like “globalist” or “marxist”. Here’s one way to find a lot of them:

There are two or or three parts to a regular expression:

- The pattern you are trying to find.

- An optional replacement, which could use part of what you’ve found in the original seeking phase.

- Options - the big one in R is

negate=TRUE, which means to match everything EXCEPT what is found.

In practice, you’ll usually save the pieces of each pattern you’ve found into a variable, then put them back together differently.

Here are two other good tutorials on regular expressions:

From Justin Meyer at a recent IRE conference that can serve as a guide.

If you’re using R, you can use a regex using the

stringrpackage (part of the tidyverse) using the functions str_detect , str_extract and their cousins. They look like this:

str_detect(var_name, regex("pattern")) - The vignette on the

stringrpackage in the Tidyverse is reasonably helpful.

23.4 Types of regular expression patterns

Literal strings

These are just letters, like “abc” or “Mary”. They are case-sensitive and no different than using text in a filter.

You can tell the regex that you want to find your pattern at the beginning or end of a line:

^ = "Find only at the beginning of a line"

$ = "Find only at the end of a line"Wild cards

A wild card is a character you use to indicate the word “anything”. Here are some ways to use wild cards in regex:

. = "any single character of any type"

.? = "a possible single character of any type (but it might not exist)"

.* = "anything or nothing of any length"

.+ = "anything one or more times"

.{1,3} = "anything running between 1 and 3 characters long"Regular expressions also have wild cards of specific types. In R, they are “escaped” using two backslashes. In other languages and in the example https://regex101.com site they only use one backslash:

\\d = "Any digit"

\\w = "Any word character"

\\s = "Any whitespace (tab, space, etc.)"

\\b = "Any word boundary" (period, comma, space, etc.)When you upper-case them, it’s the opposite:

\\D = "Anything but a digit"Character classes

Sometimes you want to tell the regex what characters it is allowed to accept. For example, say you don’t know whether there is an alternative spelling for a name – you can tell the regex to either ignore a character, or take one of several.

In R, we saw that there were alternative spellings for words like “summarize” – the British and the American spellings. You could, for example, use this pattern to pick up either spelling:

summari[sz]eThe bracket tells the regex that it’s allowed to take either one of those characters. You can also use ranges:

[a-zA-Z0-9]means that any lower case, upper case or numeric character is allowed.

Escaping

Because they’re already being used for special purposes, some characters have to be “escaped” before you can search for them. Notably, they are parentheses (), periods, backslashes, dollar signs, question marks, dashes and carets.

This means that to find a period or question mark, you have to use the pattern

\\. or

\\?In the Regex101, this is the biggest difference among the flavors of regex – Python generally requires the least amount of escaping.

Match groups

Use parentheses within a pattern to pick out pieces, which you can then use over again. The end of this chapter shows how to do this in R, which is a little complicated because we haven’t done much with lists.

23.5 Sample data

Here are three small text files that you can copy and paste from your browser into the regex101.com site. It’s a site that lets you test out regular expressions, while explaining to you what’s happening with them.

- A list of phone numbers in different formats

- A list of dates that you need to convert into a different form.

- A list of addresses that are in multiple lines, and you need to pull out the pieces. (Courtesy of IRE)

- A small chunk of the H2B visa applications from Arizona companies or worksites that has been kind of messed up for this demonstration, in tab-delimited format.

23.6 Testing and examining patterns with Regex101

Regex 101 is a website that lets you copy part of your data into a box, then test different patterns to see how they get applied. Regular expressions are very difficult to write and to read, but Regex101 lets you do it a little piece at a time. Just remember that every time you use ‘' in regex101, you will need’\` in R.

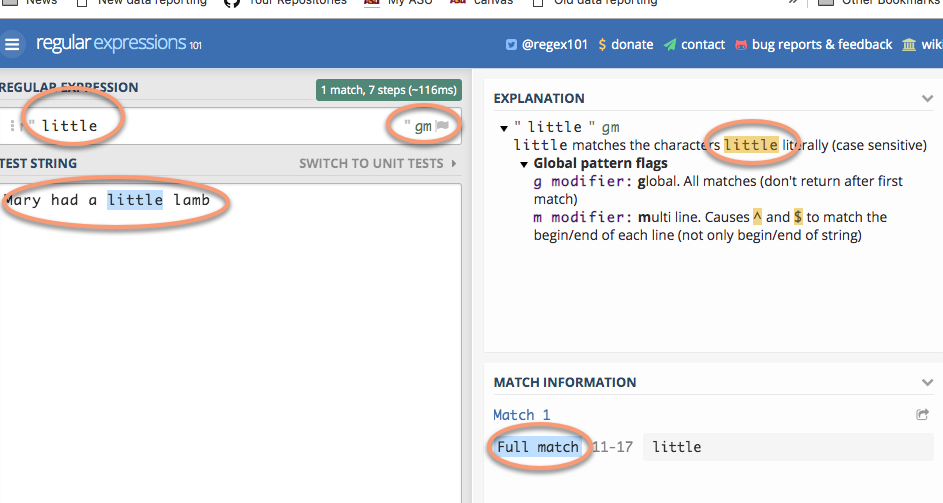

Looking for specific words or characters

The easiest regex is one that has just the characters you’re looking for when you know that they are the right case. They’re called literals because you are literally looking for those letters or characters.

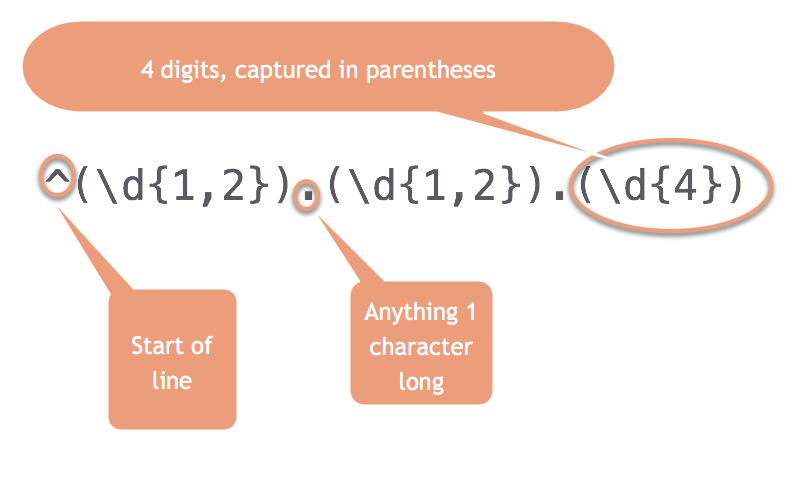

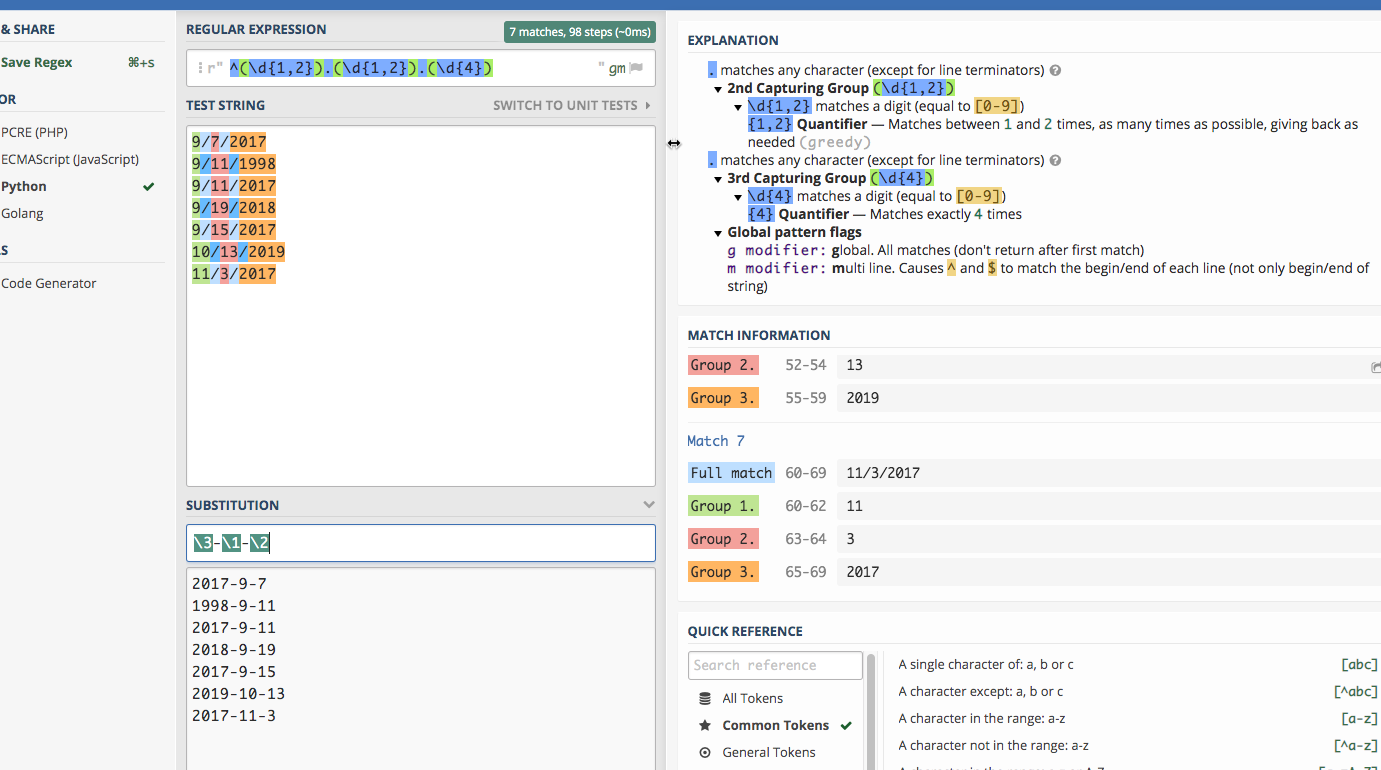

23.7 Practice #1: Extract date parts

In Regex 101, change the “Flavor” to “Python” – otherwise, you have to escape more of the characters.2

We want to turn dates that look like this:

1/24/2018into something that looks like this:

2008-1-24Copy and paste these numbers into the regex 101 window:

9/7/2017

9/11/1998

9/11/2017

9/19/2018

9/15/2017

10/13/2019

11/3/2017First, you can use any digit using the pattern “. Try to do it in pieces. First, see if you can find one or two digits at the beginning of the line.

^\d{1,2}Try coming up with the rest of it on your own before you type in the answer:

^\d{1,2}.\d{1,2}.\d{4}(This works because regular expressions normally are “greedy”. That is, if you tell it “one or two digits”, it will always take two if they exist.)

Put parentheses around any pieces that you want to use for later:

Now each piece has its section, numbered 0 for the whole match, and then 1-3 for the pieces.

23.8 Practice #2: Extract pieces of phone numbers

Here are some phone numbers in different formats:

623-374-1167

760.352.5212

831-676-3833

(831)-676-3833

623-374-1167 ext 203

831-775-0370

(602)-955-0222 x20

928-627-8080

831-784-1453This is a little more complicated than it looks, so try piecing together what this one says:

(\d{3})[-.\)]+(\d{3})[-.]+(\d{4})(This won’t work in the “substitute” area – it would be easier to create a new variable with the results than to replace the originals.)

Anything within parentheses will be “captured” in a block.

23.9 Practice #3: Extract address pieces

Here are a few lines of the data from Prof. McDonald’s tutorial, which you can copy and paste to go his exercise. (He uses the Javascript version of regular expressions, but for our purposes in this exercise, it doesn’t matter which one you use. If you choose Python, you’ll have one extra step, of putting a slash () before the quotes. The colors work a little better if you leave it on the default PHP method.)

"10111 N LAMAR BLVD

AUSTIN, TX 78753

(30.370945933000485, -97.6925542359997)"

"3636 N FM 620 RD

AUSTIN, TX 78734

(30.377873241000486, -97.9523496219997)"

"9919 SERVICE AVE

AUSTIN, TX 78743

(30.205028616000448, -97.6625588019997)"

"10601 N LAMAR BLVD

AUSTIN, TX 78753

(30.37476574700048, -97.6903937089997)"

"801 E WILLIAM CANNON DR Unit 205

AUSTIN, TX 78745

(30.190914575000477, -97.77193838799968)"

"4408 LONG CHAMP DR

AUSTIN, TX 78746

(30.340981111000474, -97.7983147919997)"

"625 W BEN WHITE BLVD EB

AUSTIN, TX 78745

(30.206884239000487, -97.7956469989997)"

"3914 N LAMAR BLVD

AUSTIN, TX 78756

(30.307477098000447, -97.74169675199965)"

"15201 FALCON HEAD BLVD

BEE CAVE, TX 78738

(30.32068282700044, -97.96890311999965)"

"11905 FM 2244 RD Unit 100

BEE CAVE, TX 78738

(30.308363203000454, -97.92393357799966)"

"3801 JUNIPER TRCE

BEE CAVE, TX 78738

(30.308247975000484, -97.93511531999968)"

"12800 GALLERIA CIR Unit 101

BEE CAVE, TX 78738

(30.307996778000472, -97.94065088199966)"

"12400 W SH 71 Unit 510

BEE CAVE, TX 78733

(30.330682136000462, -97.86979886299969)"

"716 W 6TH ST

AUSTIN, TX 78701

(30.27019732500048, -97.75036306299967)"

"3003 BEE CAVES RD

ROLLINGWOOD, TX 78746

(30.271592738000436, -97.79583786499967)"23.10 On your own

This is a small list of H2A visa applications, which are requests for agricultural and seasonal workers, from companies or worksites in Arizona. Try importing it into Excel, then copying some of the cells to practice your regular expression skills.

You might try:

- Finding all of the LLC’s in the list (limited liability companies) of names. (You should turn on the case-insensitive flag in Regex 101 or set that flag in your program if you do.)

- See how far you can get in standardizing the addresses.

- Split the city, state and zip code of the worksite.

- Find all of the jobs related to field crops such as lettuce or celery.

Yes, we might care about the case, isolating places where Trump uses all-caps. But for now let’s deal with the substance of the tweets.↩︎

Each language implements regular expressions slightly differently – when you begin to learn more languages, this will be one of the first things you’ll need to look up.↩︎