8 Verbs Part 4: Combining data

You’ll often find yourself attempting to put together two or more data sets. To add combine columns – getting more variables – use one of the join functions. To add rows – stacking datasets – use bind_rows(). This tutorial only addresses combining columns.

Reporters use joins to:

Reconstruct a typical relational database such as inspections, court data or campaign finance.

Add information from one table, such demogrphics, to another, such as a list of counties.

For clean-up operations, such as fixing company names in one table and applying the fixes to another.

Match one set of records against a completely different one to find potential stories. Some of the most famous data journalism investigations used this kind of join to find, for example, school bus drivers who have DUI’s or daycare centers run by people with serious criminal histories.

8.1 Key takeaways

- Combining two tables requires exact matches on one or more variables. Close matches don’t count.

- Whenever you can get codes to go with your data, get them – you never know when you’ll run across another dataset with the same code.

- You can use information from one table to learn more about another, especially when you have geographic information by county, Census tract or zip code.

- Many public records databases come with “lookup tables”. Be sure to request them so you can match a code, such as “G” to its translation, such as “Great!”

- When you match two datasets that weren’t intended to be combined, there will always be errors. Your job is to minimize the kind of error you fear most for a given story – false positives or false negatives.

Adding rows instead of columns

Joining only adds columns (or variables) to your data. If you need to stack tables on top of each other, use the bind_rows(data frame 1, data frame 2) function.

8.2 Concepts of joining

8.2.1 Relational databases

The world is made relational databases, which became popular in business applications as early as the 1970s. These are the data systems that your bank, your hospital or your school use to manage their very complicated businesses. The underlying concept is that, beneath the surface, each item is stored only once in a series of interconnected tables.

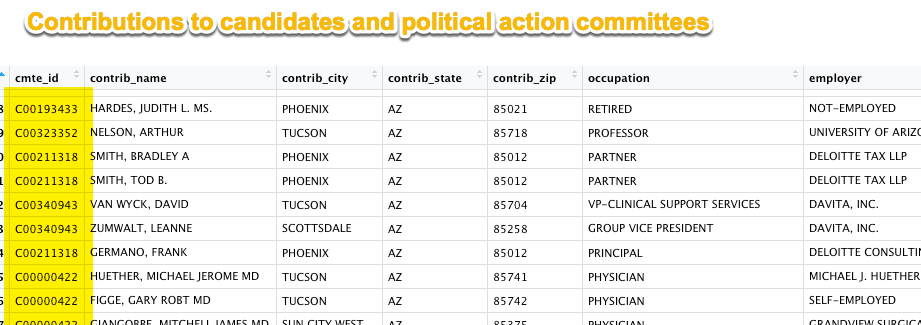

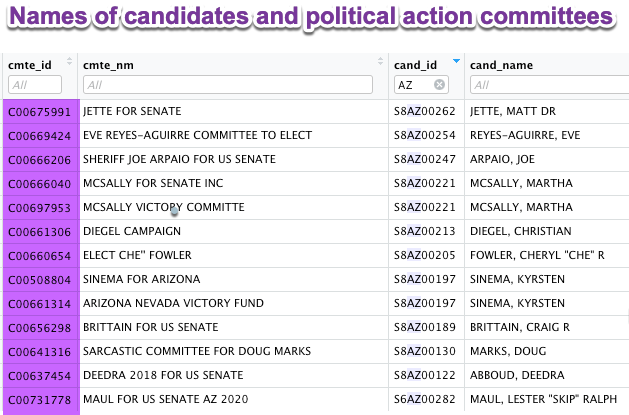

For example, the Federal Election Commission holds information about donors in one data table, and information about candidates and other political action committees in another. They link together using the common identifier of a committee ID.

Campaign finance join

Campaign finance join

(They don’t need to have the same name, and they don’t need to be in the first column.)

The key is that different nouns describe each table: the donations are one table, which list each individual transaction but don’t show the name or other information about the candidate. The candidates are in a different table, and are linked to the donations they received through a common code.

Even in this example, although Martha McSally and Kyrsten Sinema are listed twice, they are for two separate political entities.

The reason to do this is that you never have to worry that any changes to the candidate information – the treasurer, the address or the office sought – carries over to the donation. It’s only listed once in the candidate table. Most large databases are constructed this way. For example:

- Your school records are held using your student ID, which means that your address and home email only needs to be changed once, not in every class or in every account you have with the school.

- Inspection records, such as those for restaurants, hospitals, housing code violations and workplace safety, typically have at least three tables: The establishment (like a restaurant or a workplace), an inspection (an event on a date), and a violation (something that they found). They’re linked together using establishment ID’s.

- A court database usually has many types of records: A master case record links to information on charges, defendants, lawyers, sentences and court hearings.

Each table, then, is described using a different noun – candidates or contributions; defendants or cases; students or courses. This conforms to the tidy data principle that different types of information are stored in different tables.

8.3 Matchmaking with joins

To link these tables together, you’ll use the verb join. There are several ways to think of joins, but the ones you’ll most frequently use are:

inner_join: Once the two tables are fitted together using one or more columns in common, only the rows that are in BOTH of contributing tables are kept. Anything without a row is dropped. In the traditional relational database, these are the default. But in the journalism world, we use it for another purpose: matching datasets to find a needle in a haystack. You’ll see more about that later. You will often get back fewer rows than you started with in this kind of join.left_join: Once they’re all fitted together, keep everything from the first table listed and drop anything that doesn’t match from the second one. You typically use when you need to join tables that come from different agencies or systems, and you’re not sure you’ll have a good match. You should normally get back the same number of rows you started with when you use this join.

8.3.1 Matchmaking strategies

Here are several ways that reporters use joins in their stories:

“Enterprise” joins

Journalists have taken to calling a specific kind of join “enterprise”, referring to the enterprising reporters who do this. Here, you’ll look for needles in a haystack. Some of the most famous data journalism investigations relied on joining two databases that started from completely different sources, such as:

- Bus drivers who had DUI citations

- Donors to a governor who got contracts from the state

- Day care workers with criminal records

When you match these kinds of datasets, you will always have some error. You always have to report out any suspected matches, so they are time consuming stories.

In the mid-2000s, when some politicians insisted that dead people were voting and proposed measures to restrict registration, almost every regional news organization sent reporters on futile hunts for the dead voters. They got lists of people on the voter rolls, then lists of people who had died through the Social Security Death Index or local death certificates. I never met anyone who found a single actual dead voter, but months of reporter-hours were spent tracking down each lead.

It’s very common for two people to have the same name in a city. In fact, it’s common to have two people at the same home with the same name – they’ve just left off “Jr.” and “Sr.” in the database. In this case, you’ll find matches that you shouldn’t. These are false positives, or Type I errors in statistics.

Also, we rarely get dates of birth or Social Security Numbers in public records, so we have to join by name and sometimes location. If someone has moved, sometimes uses a nickname, or the government has recorded the spelling incorrectly, the join will fail – you’ll miss some of the possible matches. These are false negatives, or Type II errors in statistics.4

In different contexts, you’ll want to minimize different kinds of errors. For example, if you are looking for something extremely rare, and you want to examine every possible case – like a child sex offender working in a day care center – you might choose to make a “loose” match and get lots of false positives, which you can check. If you want to limit your reporting only to the most promising leads, you’ll be willing to live with missing some cases in order to be more sure of the joins you find.

You’ll see stories of this kind write around the lack of precision – they’ll often say, “we verified x cases of….” rather than pretend that they know of them all.

Find cases with interesting characteristics

This might be considered a join-then-filter operation. In this case, you might decide to assign each county some characteristics, such as Trump-to-Biden voting, high income or something else. Then you can pick out counties from another dataset that meet your criteria.

This is common when you have data by zip code or some other geography, and you want to find clusters of interesting potential stories, such as PPP loans in minority neighborhoods.

Summarise data against another dataset

This would be considered grouping-then-joining. You count the number of loans in each zip code so that you can calculate a rate – the amount per household, or something like it.

8.4 Arizona immunization data

I looked up the information from most of the public and charter schools in Arizona against Department of Education statistics to find their federal ID numbers, then downloaded some characteristics of schools from the National Center for Education Statistics characteristics. I effectively created a relational database (with a few errors) by assigning unique codes to each school in the immunization data.

You may do that a lot yourself. For example, you might have to look up Zip Codes to match against Census data, or you might have to look up DUNS numbers to match company names across databases. There are ways to do this using a computer and “fuzzy matching”, but it always involves at least a little work by hand.

Two tables are saved in the R dataset called immune_to_nces.Rda, which you can add to your environment using the load() command.

load (url("https://github.com/cronkitedata/rstudyguide/blob/master/data/immune_to_nces.Rda?raw=true"))- You can load R datasets from the web through the

urlfunction, as above.

There are 2,414 schools in the NCES database, but only 841 schools in the immunizations because we’ve only kept schools that had students in Grade 6. There were seven schools that I couldn’t find in the NCES data, and their IDs are blank.

Here are their variables:

glimpse(grade6_to_nces)## Rows: 841

## Columns: 17

## $ rowid <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,…

## $ nces_id <chr> "040906000652", "040906000915", "040079703230", "0…

## $ school_name <chr> "ABRAHAM LINCOLN TRADITIONAL SCHOOL", "ACACIA ELEM…

## $ address <chr> "10444 N 39TH AVE", "3021 W EVANS DR", "7102 W VAL…

## $ city <chr> "PHOENIX", "PHOENIX", "TUCSON", "TUCSON", "PHOENIX…

## $ county <chr> "MARICOPA", "MARICOPA", "PIMA", "PIMA", "MARICOPA"…

## $ zip_code <chr> "85051", "85053", "85757", "85705", "85033", "8501…

## $ school_nurse <chr> "NO", "YES", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "…

## $ school_type <chr> "PUBLIC", "PUBLIC", "CHARTER", "CHARTER", "CHARTER…

## $ enrolled <dbl> 59, 134, 53, 42, 113, 56, 75, 44, 45, 106, 53, 87,…

## $ num_immune_mmr <dbl> 58, 134, 52, 40, 113, 55, 73, 39, 44, 105, 46, 84,…

## $ num_exempt_mmr <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 1, 7, 3, 0, 0, 0, 2, 2,…

## $ num_compliance_mmr <dbl> 59, 134, 53, 42, 113, 56, 75, 44, 45, 106, 53, 87,…

## $ num_pbe <dbl> 5, 2, 1, 0, 3, 6, 4, 0, 23, 4, 9, 3, 1, 1, 0, 4, 0…

## $ num_medical_exempt <dbl> 2, 0, 0, 7, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0,…

## $ num_pbe_exempt_all <dbl> 5, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 2, 1, 10, 3, 0, 0, 0, 2, 2…

## $ match_type <chr> "Yes", "Manual", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes"…glimpse (nces_master)## Rows: 2,414

## Columns: 15

## $ rowid <int> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,…

## $ nces_school_id <chr> "040553000451", "040463000999", "040010601892", "0…

## $ nces_district_id <chr> "0405530", "0404630", "0400106", "0400417", "04067…

## $ nces_district_name <chr> "Nogales Unified District", "Marana Unified Distri…

## $ nces_school_name <chr> "A J MITCHELL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL", "A. C. E.", "AAE…

## $ nces_school_type <chr> "1-Regular school", "1-Regular school", "1-Regular…

## $ nces_urban <chr> "33-Town: Remote", "41-Rural: Fringe", "11-City: L…

## $ nces_student_ct <dbl> 406, 10, 313, 444, 517, 608, 868, 643, NA, 61, 59,…

## $ nces_fte_teacher <dbl> 20.50, 6.80, NA, NA, 25.60, 32.75, 45.87, 0.00, NA…

## $ nces_ratio <dbl> 19.80, 1.47, NA, NA, 20.20, 18.56, 18.92, NA, NA, …

## $ nces_lowest <chr> "Kindergarten", "7th Grade", "9th Grade", "9th Gra…

## $ nces_highest <chr> "5th Grade", "12th Grade", "12th Grade", "12th Gra…

## $ nces_school_level <chr> "Elementary", "High", "High", "High", "Elementary"…

## $ nces_county_name <chr> "Santa Cruz County", "Pima County", "Maricopa Coun…

## $ nces_fips <chr> "04023", "04019", "04013", "04013", "04025", "0401…8.4.1 Setting up the data

In this case, we want to get information that the federal government had on the schools attached to the immunization data. In particular, we’d like to be able to generate statistics by district, by urbanization and type of school, and we’d like to keep the code for the county so we can link it up to other datasets.

To make it simple, I’ll just create a small set of data for each table:

immune <-

grade6_to_nces %>%

select (rowid, nces_id, school_name, city, county, zip_code, school_nurse, school_type,

enrolled, num_immune_mmr)

school_list <-

nces_master %>%

select (nces_school_id, nces_district_id, nces_district_name, nces_school_type,

nces_urban, nces_ratio, nces_school_level, nces_fips)8.4.2 Apply the join

Here are two ways to join:

immune %>%

inner_join (school_list, by=c("nces_id" = "nces_school_id")) %>%

glimpse ()## Rows: 834

## Columns: 17

## $ rowid <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,…

## $ nces_id <chr> "040906000652", "040906000915", "040079703230", "0…

## $ school_name <chr> "ABRAHAM LINCOLN TRADITIONAL SCHOOL", "ACACIA ELEM…

## $ city <chr> "PHOENIX", "PHOENIX", "TUCSON", "TUCSON", "PHOENIX…

## $ county <chr> "MARICOPA", "MARICOPA", "PIMA", "PIMA", "MARICOPA"…

## $ zip_code <chr> "85051", "85053", "85757", "85705", "85033", "8501…

## $ school_nurse <chr> "NO", "YES", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "…

## $ school_type <chr> "PUBLIC", "PUBLIC", "CHARTER", "CHARTER", "CHARTER…

## $ enrolled <dbl> 59, 134, 53, 42, 113, 56, 75, 44, 45, 106, 53, 87,…

## $ num_immune_mmr <dbl> 58, 134, 52, 40, 113, 55, 73, 39, 44, 105, 46, 84,…

## $ nces_district_id <chr> "0409060", "0409060", "0400797", "0400368", "04009…

## $ nces_district_name <chr> "Washington Elementary School District", "Washingt…

## $ nces_school_type <chr> "1-Regular school", "1-Regular school", "1-Regular…

## $ nces_urban <chr> "11-City: Large", "11-City: Large", "21-Suburb: La…

## $ nces_ratio <dbl> 18.56, 18.92, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 19.13, N…

## $ nces_school_level <chr> "Elementary", "Elementary", "Elementary", "Other",…

## $ nces_fips <chr> "04013", "04013", "04019", "04019", "04013", "0401…You can see that the information from the federal Education Department was added to the immunization data, but we lost seven records – the seven that I couldn’t find in the federal department.

To preserve these records, you’ll usually protect one of the tables – the one you care about most – and keep everything, even if it doesn’t match. To do that, use a left or right join, depending on whether you mention the table first or second. In this case:

immune_joined <-

immune %>% # the table I want to protect

left_join ( school_list, # the table I want to apply to my original data frame

by=c("nces_id"="nces_school_id") ) # the variable that is the same in the two tables.

glimpse(immune_joined)## Rows: 841

## Columns: 17

## $ rowid <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,…

## $ nces_id <chr> "040906000652", "040906000915", "040079703230", "0…

## $ school_name <chr> "ABRAHAM LINCOLN TRADITIONAL SCHOOL", "ACACIA ELEM…

## $ city <chr> "PHOENIX", "PHOENIX", "TUCSON", "TUCSON", "PHOENIX…

## $ county <chr> "MARICOPA", "MARICOPA", "PIMA", "PIMA", "MARICOPA"…

## $ zip_code <chr> "85051", "85053", "85757", "85705", "85033", "8501…

## $ school_nurse <chr> "NO", "YES", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "NO", "…

## $ school_type <chr> "PUBLIC", "PUBLIC", "CHARTER", "CHARTER", "CHARTER…

## $ enrolled <dbl> 59, 134, 53, 42, 113, 56, 75, 44, 45, 106, 53, 87,…

## $ num_immune_mmr <dbl> 58, 134, 52, 40, 113, 55, 73, 39, 44, 105, 46, 84,…

## $ nces_district_id <chr> "0409060", "0409060", "0400797", "0400368", "04009…

## $ nces_district_name <chr> "Washington Elementary School District", "Washingt…

## $ nces_school_type <chr> "1-Regular school", "1-Regular school", "1-Regular…

## $ nces_urban <chr> "11-City: Large", "11-City: Large", "21-Suburb: La…

## $ nces_ratio <dbl> 18.56, 18.92, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, 19.13, N…

## $ nces_school_level <chr> "Elementary", "Elementary", "Elementary", "Other",…

## $ nces_fips <chr> "04013", "04013", "04019", "04019", "04013", "0401…Here are the rows that were kept without a match:

| rowid | nces_id | school_name | city | county | zip_code | school_nurse | school_type | enrolled | num_immune_mmr | nces_district_id | nces_district_name | nces_school_type | nces_urban | nces_ratio | nces_school_level | nces_fips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | NA | ARCADIA NEIGHBORHOOD LEARNING CENTER | SCOTTSDALE | MARICOPA | 85251 | YES | PUBLIC | 52 | 49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 209 | NA | DENNEHOTSO BOARDING SCHOOL | DENNEHOTSO | APACHE | 86535 | NO | PUBLIC | 21 | 21 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 414 | NA | J.C.U.S.D. - JOSEPH CITY PRESCHOOL | JOSEPH CITY | NAVAJO | 86032 | NO | PUBLIC | 33 | 28 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 452 | NA | L.H.U.S.D. #1 - DEVELOPMENTAL PRESCHOOL | LAKE HAVASU CITY | MOHAVE | 86403 | YES | PUBLIC | 69 | 67 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 522 | 590014800009 | MANY FARMS COMMUNITY SCHOOL, INC | MANY FARMS | APACHE | 86538 | NO | PUBLIC | 38 | 38 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 785 | NA | ST THERESA LITTLE FLOWER PRESCHOOL | PHOENIX | MARICOPA | 85018 | YES | PUBLIC | 42 | 42 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 821 | NA | T.U.S.D.#1 - C. E. ROSE PRESCHOOL PROGRAM | TUCSON | PIMA | 85714 | YES | PUBLIC | 86 | 86 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

In real life, you’d have to decide how much you care about these missing schools – does it ruin your story, or can you just mention that you were unable to get information for a handful of schools, amounting to about 350 students?

8.4.3 Use the joined table

Now I might want to look at which school districts have low immunization rates:

immune_joined %>%

# by school

mutate (school_pct = num_immune_mmr / enrolled * 100 ) %>%

# by district

group_by (nces_district_name, county) %>%

summarise ( num_schools = n() ,

total_enrolled = sum(enrolled),

total_immune = sum (num_immune_mmr),

median_immune = median (school_pct)

) %>%

# district total pct (immunized / total students)

mutate ( pct_immune = total_immune/ total_enrolled * 100) %>%

select (nces_district_name, county, num_schools, pct_immune, total_enrolled, median_immune) %>%

filter (median_immune <= 93) %>%

head (10) %>%

kable (digits=1)## `summarise()` has grouped output by 'nces_district_name'. You can override using the `.groups` argument.| nces_district_name | county | num_schools | pct_immune | total_enrolled | median_immune |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acclaim Charter School | MARICOPA | 1 | 88.6 | 44 | 88.6 |

| American Leadership Academy Inc. | MARICOPA | 5 | 91.9 | 467 | 92.9 |

| Arete Preparatory Academy | MARICOPA | 1 | 90.9 | 99 | 90.9 |

| Arizona Connections Academy Charter School Inc. | MARICOPA | 1 | 85.6 | 201 | 85.6 |

| Arizona Montessori Charter School at Anthem | MARICOPA | 1 | 86.5 | 37 | 86.5 |

| Ball Charter Schools (Dobson) | MARICOPA | 1 | 90.0 | 40 | 90.0 |

| BASIS School Inc. 12 | YAVAPAI | 1 | 85.7 | 91 | 85.7 |

| BASIS School Inc. 6 | COCONINO | 1 | 92.6 | 95 | 92.6 |

| BASIS School Inc. 9 | MARICOPA | 1 | 91.7 | 133 | 91.7 |

| Benchmark School Inc. | MARICOPA | 1 | 85.5 | 55 | 85.5 |

8.5 Joining risks

8.5.1 joining tl;dr

There are lots of risks in joining tables that you created yourself, or that were created outside a big relational database system. Keep an eye on the number of rows returned every time that you join – you should know what to expect.

8.5.2 Double counting with joins

We won’t go into this in depth, but just be aware it’s easy to double-count rows when you join. Here’s a made-up example, in which a zip code is on the border and is in two counties:

Say you want to use some data on zip codes :

| zip code | county | info |

|---|---|---|

| 85232 | Maricopa | some data |

| 85232 | Pinal | some more data |

and match it to a list of restaurants in a zip code:

| zip code | restaurant name |

|---|---|

| 85232 | My favorite restaurant |

| 85232 | My second-favorite restaurant |

When you match these, you’ll get 4 rows:

| zip code | county | info | restaurant name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 85232 | Maricopa | some data | My favorite restaurant |

| 85232 | Pinal | some more data | My favorite restaurant |

| 85232 | Maricopa | some data | My second-favorite restaurant |

| 85232 | Pinal | some more data | My second-favority restaurant |

Now, every time you try to count restaurants, these two will be double-counted.

In computing, this is called a “many-to-many” relationship – there are many rows of zip codes and many rows of restaurants. In journalism, we call it spaghetti. It’s usually an unintended mess.

8.5.3 Losing rows with joins

The opposite can occur if you aren’t careful and there are items you want to keep that are missing in your reference table. That’s what happened in the immunization data above for the seven schools that I couldn’t find.

8.6 Resources

The “Relational data” chapter in the R for Data Science textbook has details on exactly how a complex data set might fit together.

An example using a superheroes dataset, from Stat 545 at the University of British Columbia

8.6.1 Practice

Immunization data

Create a new table from the immunizations and DOE data used in this example, then see if you can find any patterns in immunization rates by school district rather than by county. (Note that charter school companies are each their own district.) Do the same by looking at urban vs. rural schools.

Campaign finance data

There are two tables saved in the R data file, “azcampfin.Rda”. One holds information on contributions available from the offiical FEC database as of Feb. 23, 2020 and the other holds information on the candidates and committees.

The following codes are used in this dataset, which you may want to save into data frame. Here is some code you can use to create a lookup table for the transaction types. These codes can be joined with the column called transaction_tp in the contributions (or arizona20) data frame.

transaction_types <- tribble (

~tcode, ~contrib_type,

"10", "To a Super PAC",

"11", "Native American tribal",

"15", "Individual contrib",

"15C", "From a candidate",

"15E", "Earmarked (eg, ActBlue)",

"20Y", "Non-federal refund",

"22Y", "Refund to indiv.",

"24I", "Earmarked check passed on",

"24T", "Earmarked contrib passed on",

"30", "To a convention account",

"31", "To a headquarters account",

"32", "To a recount effort",

"41Y", "Refund from headquarters account"

)(These are pretty complicated definitions in the federal campaign finance world. For now, don’t worry much about what they mean. Refunds are shown in the data as negative numbers, which is what you want.)

Try to analyze some of this by putting together the datasets and finding interesting items or patterns.

I remember them by thinking of the boy who cried wolf. When the village came running and there was no wolf, it was a Type I error, or false positive ; when the village ignored the boy and there was a wolf, it was a Type II error, or false negative.↩︎